The Coptic Orthodox Church announced this month that it had suspended dialogue with the Catholic Church due to Pope Francis’ decision. Fiducia Suppliants – which Coptic leaders saw as a Catholic “change in position” on homosexuality.

In a March 7 statementthe synod of Coptic Orthodox bishops announced that it had decreed to “suspend the theological dialogue with the Catholic Church, reassess the results obtained by the dialogue since its beginnings 20 years ago and establish new norms and mechanisms so that the dialogue continues in the future.”

“The Coptic Orthodox Church affirms its firm position of rejecting all forms of homosexual relations, because they violate the Holy Bible and the law by which God created man as male and female, and the Church considers any form of homosexual relationship, whatever its type, to be a blessing. be a blessing for sin, and this is unacceptable,” the bishops said.

The Coptic ruling attracted attention from Catholics, some of whom said it suggested that the December decree motu proprio Fiducia suppliants was ill-advised.

But what is the Coptic Orthodox Church? Has his ecumenical dialogue with Catholics really brought anything?

The pillar explain.

What is the Coptic Orthodox Church?

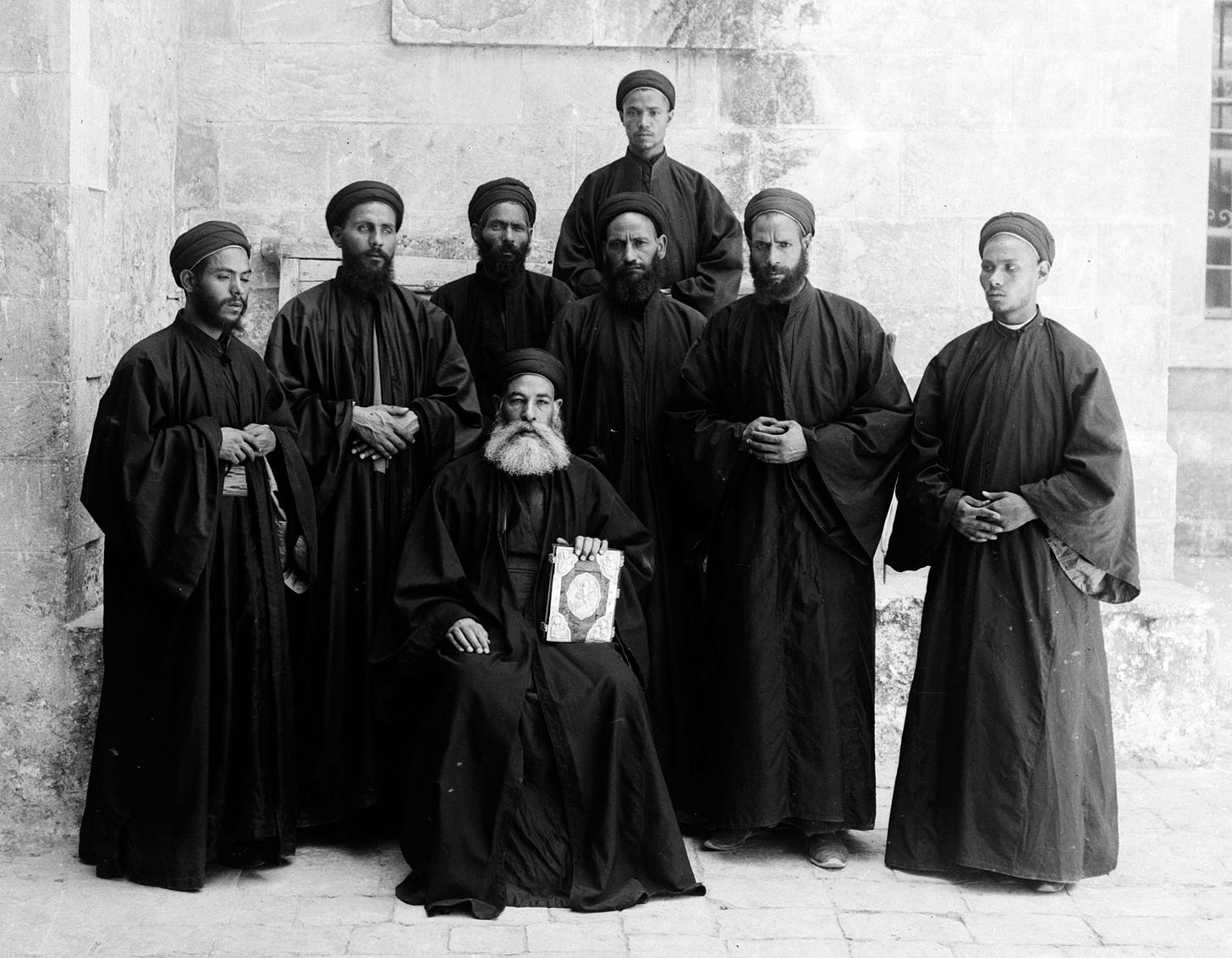

The Coptic Orthodox Church is an Orthodox Church present mainly in North Africa and in regions of the world where North Africans have migrated.

The Church, which has apostolic succession and valid sacraments, has at least 10 million members, and perhaps double that, led by more than 100 bishops.

How did it start?

According to early Christian traditions, Saint Mark the Evangelist was a traveling companion of Saint Barnabas and Saint Peter. He is considered the author of the Gospel of Mark, which is believed to have been composed largely from Peter’s memories and kerygmatic preaching.

After his missionary journeys, tradition has it that Saint Mark traveled to Alexandria, Egypt, then one of the largest and most important cities in the world. Mark became the bishop of the growing Christian community and is recorded in Christian history and liturgy as a martyr – although the details of his martyrdom are unclear.

In the decades that followed, Christianity spread across Egypt and the Nile Valley, with Coptic, the Egyptian language, as the primary liturgical language, and a unique liturgical rite emerging from the region.

Although Egyptian Christians faced persecution in their early decades, this intensified at the beginning of the third century, under the orders of the emperors of Rome.

In the early 4th century, hundreds of thousands of Christians were martyred in Egypt, as the empire attempted to eradicate Christianity from the region. In fact, today the Coptic Church begins its calendar from a particularly egregious year of persecution in Egypt, 248 AD. The Coptic calendar uses the AM demarcation — Anno Martyrii, rather than AD, Anne Domini.

During the same early centuries, the see, or diocese, of Alexandria became known as an important center of Catholic thought, life, and spirituality.

In the Christian world, a Christological controversy emerged in the 440s over the teaching of a monk named Eutyches, whose Christology seemed to many to deny the humanity of Jesus Christ, suggesting that the humanity of the Lord was encompassed or absorbed by its divinity.

(Editor’s note: Historical theologians, The pillar is aware that the thickets of Christology are full of possibilities for error. Our goal is to simply present a deeply complex reality and we appreciate your patience.)

The Eutychian controversy was part of a theological movement eventually called Monophysitism, in which several schools of theology taught – in various ways – that Christ had only one nature, his divine nature.

The controversy over Monophysitism eventually led to the Council of Chalcedon in 451, attended by more than 500 bishops from across the Church.

The council condemned Monophysitism, confirming that Jesus Christ possessed both human and divine nature, united in one person.

But the council was also influenced and plagued by politics, and sometimes by misunderstandings about the positions of various Church leaders.

The bishops of Egypt claim to have been misunderstood by the bishops of Constantinople and Rome during the council, their Christology being unfairly equated with that of Eutyches. They viewed their Christology – called Miaphysitism – as different, because it held that Christ had a united divine-human nature, not a singular divine nature.

Nevertheless, the Egyptian bishops were grouped at the Council of Chalcedon with other bishops considered Monophysites, which led to a break in the communion of the Church.

Indeed, the patriarch of Alexandria, Dioscorus, refused to accept the council’s Christological decrees, arguing that even if Eutyches were to be condemned, the language of Chalcedon could lead to further theological heresies.

The story from there is complicated and takes place over centuries. But the divide in communion that began in Chalcedon calcified over subsequent centuries, such that a group of Orthodox churches in India, Syria, Egypt, Ethiopia and Armenia became institutionally distinct of Christian communion in the East, centered around Constantinople, and in the West, centered around Rome.

(Editor’s note: Armenia’s ecclesiastical history is actually more complicated than that, but that’s probably an entirely different explanation..)

Eventually, this group of churches became known as the Eastern Orthodox Churches – the Coptic Orthodox Church being among the largest.

The seven Eastern Orthodox Churches are in a kind of ecclesial communion with each other, but not with the Eastern Orthodox Churches nor with the Catholic communion. The largest of the Eastern Orthodox Churches is the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, which has between 40 and 50 million members.

What does the Coptic liturgy look like?

Good question. Coptic liturgy is pretty cool, if you want The pillar‘s take on the subject.

Coptic Orthodox Christians offer a liturgy according to the Coptic, or Alexandrian, rite, which developed in and around Alexandria during the early centuries of the Church, and developed to follow three different liturgical missals at different times of the year.

Liturgies are celebrated in Coptic, Arabic, English and other languages of the Egyptian Coptic diaspora.

Here is a Coptic liturgy which takes place partially in English:

Are there Coptic Catholics?

Yes, the Coptic Catholic Church is a sui iuris Eastern Catholic Church with some 200,000 members, headquartered in Cairo.

The modern history of the Church begins with the Catholic conversion in 1741 of Coptic bishop Anba Athanasius, who was soon after appointed vicar apostolic of a very small community of Egyptian Catholics who observed Coptic liturgical customs.

While Anba Athanasius eventually returned to Orthodoxy, the Vatican continued to appoint vicars apostolic for Egyptian Catholics using the Coptic liturgy.

In 1895, Pope Leo XIII gave these Coptic Catholics a more formal status, appointing Bishop Cyril Makarios as Patriarch of Alexandria of the Copts, thus confirming the status of a sui iuris Eastern Catholic jurisdiction. Soon after, Cyril held a synod of other Coptic Catholic bishops, thus cementing the emerging country’s governmental structure. sui iuris Church.

Today, Coptic Catholics have parishes in Italy, France, Canada, the United States, Australia, Kuwait and, of course, Egypt.

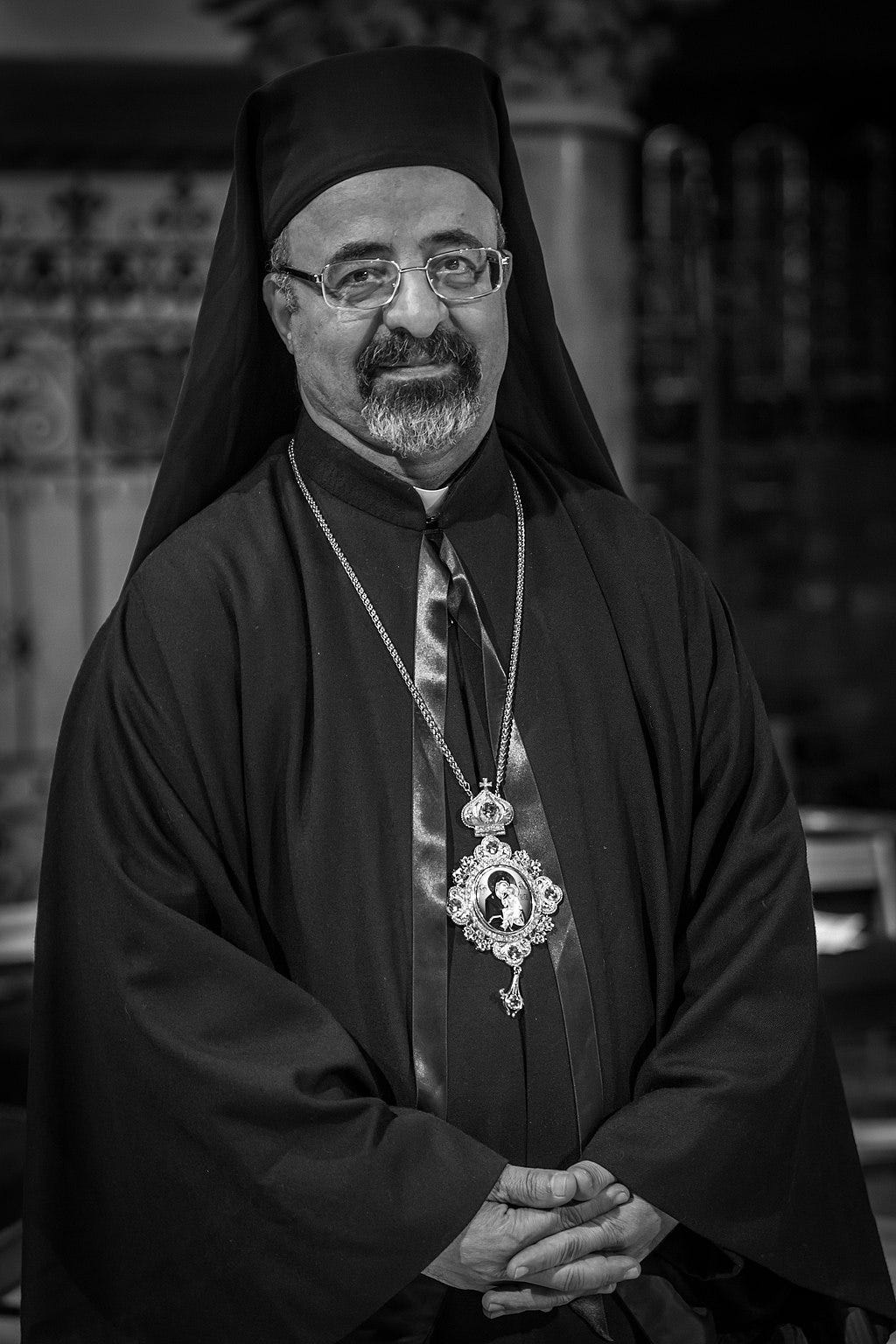

The current head of the Coptic Catholic Church is Patriarch Ibrahim Isaac Sidrak.

Is it important that the Coptic Orthodox have suspended dialogue with the Catholics?

It’s up to you, of course.

But over the past several decades, the Coptic Orthodox Church and the Catholic Church have had a long and productive conversation about Christology.

In 1972, Pope Saint Paul VI and Coptic Pope Shenouda III of Alexandria reached a joint agreement declaration that:

“We confess that our Lord and God and Savior and King of us all, Jesus Christ, is God perfect in His Godhead, perfect man in His humanity. In Him, his divinity is united with his humanity in a real and perfect union, without mixture, without mixture, without confusion, without alteration, without division, without separation. His divinity did not separate from his humanity for a moment, not a blink of an eye. He who is eternal and invisible God became visible in the flesh and took the form of a servant. In Him are preserved all the properties of divinity and all the properties of humanity, together in a real, perfect, indivisible and inseparable union.

After this declaration, a formal theological dialogue was established, and in 1988 a joint commission published another statement on Christology:

“We believe that our Lord, God and Savior Jesus Christ, the Logos incarnate, is perfect in his divinity and perfect in his humanity. He made His Humanity one with His Divinity, without admixture, mixing, or confusion. His Divinity was not separated from His Humanity, even for a moment or a blink of an eye. At the same time we anathematize the doctrines of Nestorius and Eutyches. »

Since Orthodox Copts claim that their Christology was misunderstood in Chalcedon, finding ways to express a common theology of Christ with Catholics has been seen by many ecumenists as a big deal. And although many other issues must be resolved before true ecclesial communion between Rome and Alexandria, an agreement on Jesus is widely seen as an important first step.

What will happen now?

In 2003, a joint committee between the Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Churches was established, the first meeting of which was held in Cairo. Nearly 20 official meetings have taken place since then, with conversations focused on the sacraments.

The Coptic Orthodox declaration of March 7 effectively suspends Coptic participation in this group. For now, many ecumenical experts are looking to Ethiopia for the next step. If the Ethiopian Orthodox also suspend their participation, most experts will consider the dialogue effectively dead. But for now, it is unclear when the Ethiopian Orthodox bishops might take up the issue.

In January, Pope Francis told the Joint International Commission for Theological Dialogue between the Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Churches that they should engage in a three-way conversation.

“The dialogue of charity, the dialogue of truth and the dialogue of life: three inseparable ways of moving forward on the ecumenical path that your commission has encouraged over the last 20 years,” the pope told the commission.