Evangelical Christians — a key voting bloc for former President Donald Trump — have influenced the nation’s religious, cultural and political discourse for decades.

But a new book explores the growing divide among evangelicals. One side is increasingly political and attracting members, while the other is losing members as it seeks to stay out of partisan politics.

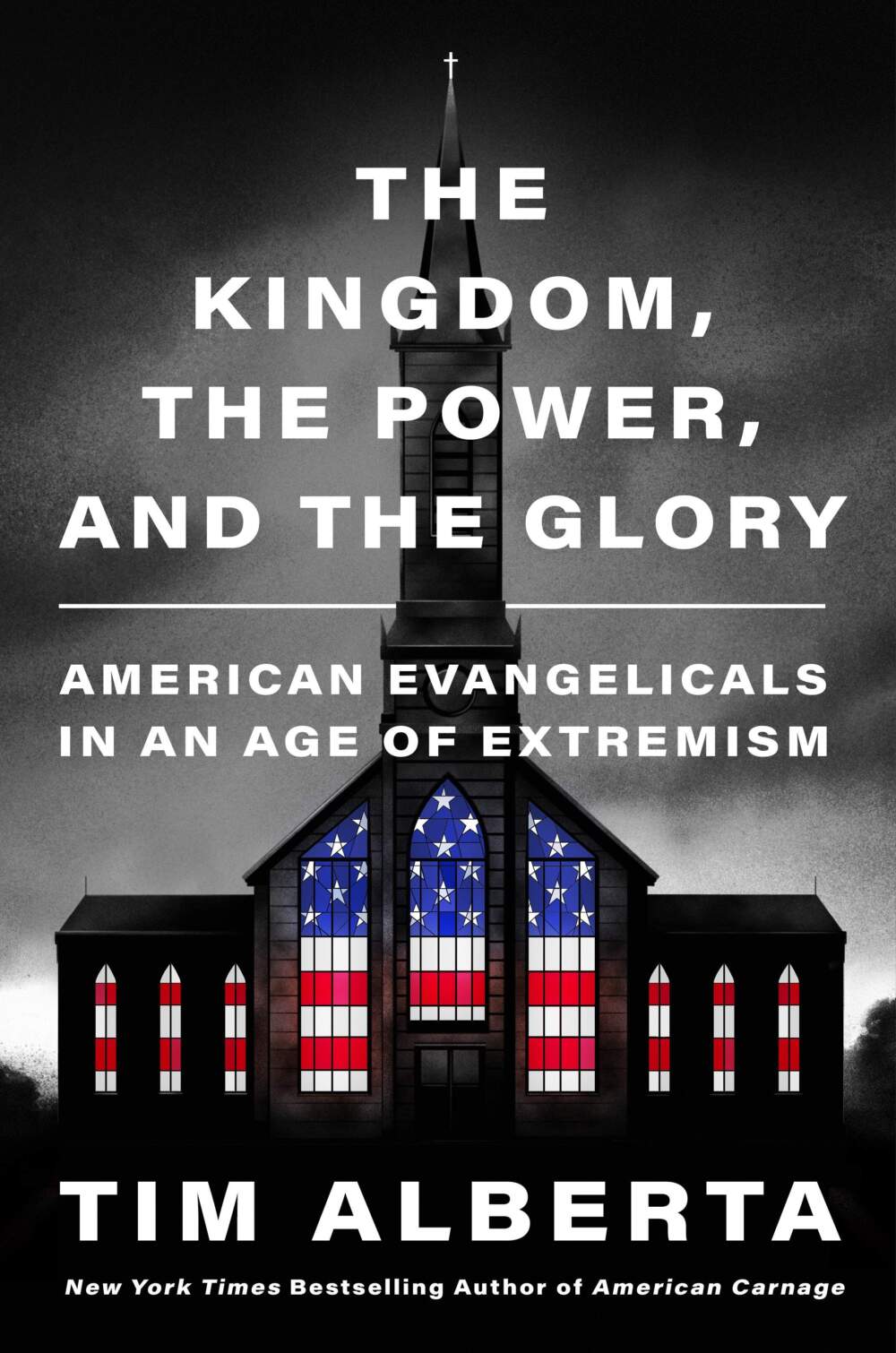

Atlantic Tim Alberta recounts a personal journey in his new book, “Kingdom, Power, and Glory: American Evangelicals in the Age of Extremism.” Alberta is an award-winning journalist who grew up in an evangelical church.

The son of a pastor who grew up in the conservative town of Brighton, Michigan, Alberta faced backlash from right-wing media after the publication of a book about Trump’s rise to power within the Republican Party at the time of his father’s death, he said. He faced a confrontation at the funeral after returning to his hometown evangelical church, where his father served as pastor for nearly 30 years.

“There were people who wondered if I was still a Christian because of the way I criticized Donald Trump,” Alberta says. “And it was an eye-opening experience to say the least.”

Excerpt from the book: “The Kingdom, the Power and the Glory”

By Tim Alberta

Prologue

Standing at the back of the sanctuary, my three older brothers and I formed a receiving line. Cornerstone was a small church when we arrived as children. No more. Brighton, once a sleepy town at the intersection of two highways, had become a popular spot for commuters heading to Detroit and Ann Arbor. Meanwhile, Dad, with his baseball allegories and Greek linguistics classes, had built a reputation for his oratory from the pulpit. By the time I moved in 2008, Cornerstone had grown from a few hundred members to a few thousand.

Now the crowds crowded around us, filling the sanctuary and spilling into the narthex, where tables displayed flowers, golf clubs, and photos of Dad. I was numb. My brothers too. Neither of us had slept much that week. So the first time someone made a quick reference to Rush Limbaugh, it didn’t register. But then another person raised him. And then another. That’s when I connected the dots. Apparently the king of conservative radio had recently dubbed me on his show – “A Guy Named Tim Alberta” – and was describing my book’s unflattering revelations about President Trump. Nothing at that moment could have mattered less to me. I smiled, shrugged, and thanked them for coming to the tour.

They kept coming. More than I could count. People from the Church—people I had known my entire life—greeted me, not primarily with condolences or encouragement or mourning, but with comments about Rush Limbaugh and Donald Trump. Some of it was playful, with the guys remarking on how I was the same troublemaker they’d known since kindergarten. But some of them weren’t playful. Some were angry; some were cold and confrontational. A man wondered if I was really a Christian. Another asked me if I was still “on the good side.” While Dad was in a box a hundred yards away.

It got to the point where I had to take a walk. Righteous anger was

begins to break through the fog of melancholy. It was like a bad dream inside

from a bad dream. Here in our place of worship, people taunted me

about politics while I was trying to mourn my father. I was in the company of

some friends that day who didn’t profess to know Jesus, and yet they enveloped me in peace and comfort. Some of these card-carrying evangelical Christians. Not really. They did not see a son suffering; they saw a vulnerable opponent.

That night, as I perfected the eulogy I would deliver the next afternoon, I still felt the pain. My wife felt it too. Unfazed in the family, she encouraged me to be careful with my words and warned me against mentioning the unpleasantness of the day. I followed half of his advice.

In front of a packed crowd on August 2, 2019, I paid tribute to the man who taught me everything: how to throw a baseball, how to be a gentleman, how to trust and love the Lord. Reciting my favorite verse, from Paul’s second letter to the early church in Corinth, Greece, I spoke of Dad’s instructions to keep our eyes fixed on what we could not see. Reading his favorite poem, about a man named Richard Cory, I recounted Dad’s warning that we could accumulate great wealth and still remain poor.

Then I recounted all the people who had approached me a day earlier, wanting to discuss Trump’s wars on AM radio. I spoke about the need for discipleship and spiritual formation. I suggested that their time in the car would be better spent listening to Dad’s old sermons. If they needed help finding biblical listening for their daily commute, I suggested with some sarcasm that the staff pastors could help. “Why do you listen to Rush Limbaugh?” I asked my father’s congregation. “Garbage goes in, garbage goes out.”

There was nervous laughter in the sanctuary. Some people were visibly agitated. Others looked away, pretending not to hear. My father’s successor, a young pastor named Chris Winans, had a shocked expression. Never mind. I had said my article. It was finished. At least that’s what I thought. A few hours later, after burying Dad, my brothers and I plopped down on the couches in our parents’ living room. We cracked open a few beers and threw a baseball game. Behind us in the kitchen, a small group of church ladies were busy preparing a meal for the family. Here, I thought, is the love of Christ. As I watched them hustle, comfort mom, and tend to her sons, I found myself regretting Rush Limbaugh’s remark. Most of the people in our church were humble, caring Christians like these ladies. Maybe I overdid things.

This segment aired on January 30, 2024.