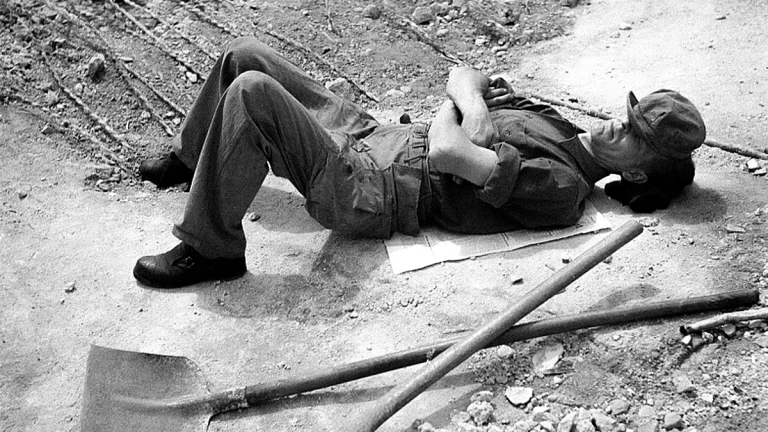

Everywhere we look, we see people pushing their bodies, their minds, and their capacity for faithfulness and fruitfulness to their limits. In a way, society encourages this “all the way” lifestyle: if you want to move forward, this is the price you have to pay.

But in another way, society demands this lifestyle. People at the lower end of our socio-economic scale feel this more acutely, but no one is immune. Whatever the reason, we are trapped by our productivity systems and we take everything we can from ourselves, burning the proverbial candle at both ends.

If you’ve ever thought, Enough is enough!– quietly protesting demands your body can’t meet – you’re certainly not alone. I struggle with these feelings regularly, sorting out my values and priorities, wondering if I’m conceding an entire good life to the superficial aspirations of a relentless consumer society.

This is why I feel grateful for the gift of the Sabbath. The Sabbath is God’s way of saying: Enough is enough.

The Sabbath is an invitation to orient our lives around a different rhythm of practice, one that recognizes the moral limit to what we should expect from our bodies and our lives, and the potential for profit we should derive from ourselves. themselves and others.

Walter Brueggemann remind us this Sabbath is framed through the stories of Creation and Exodus. Scripture first defines the seventh day as God resting from the work of creation (Genesis 1). Is it because God does not have the capacity to continue? Barely! Instead, God models for all of creation the idea that there is a moral limit to the demands of production. God invites people to join in his rest to rejoice in creation. The seventh day is a regular rhythmic reminder of God’s abundance and an invitation to celebration.

Scripture also presents the Sabbath as a direct response to God’s liberation of the Egyptian people from slavery (Deut. 5). In the context of generations of economic exploitation, where God’s people were seen as production units building the storehouses of Pharaoh’s wealth, the Sabbath is also an invitation from God to experience freedom and restoration from the effects of immoral extraction and unjust exploitation.

The Sabbath finds its meaning in the generative and liberating power of God. Perhaps this is why the command in Exodus 20:8 is to “remember the Sabbath day by keeping it holy.” The sanctity of the Sabbath is meant to be a coherent rehearsal of God’s great story and our invitation to join in it.

Practicing the Sabbath involves patterns of life that rejoice in God’s abundance and place us in the flow of God’s restoration. These one-day-a-week Sabbath spiritual practices are helpful in taking us away from the demands of production and helping to foster a life of celebration and restoration.

But there is more than that, for the Sabbath is not just for people; The Sabbath is for people.

The Sabbath was not designed by God for isolated individuals but as a reset for the community. Beyond the laws governing the weekly day of rest, the scriptural practice of the Sabbath included a regular rhythm of redressing society-wide economic injustice.

Every seven years, God required debts to be forgiven – a way to ensure that the poor were not exploited. Even more, God required that debts not only be forgiven but, because they often arose from personal economic calamities, include generous gifts of wealth to former debtors. These gifts were celebrations of abundance (there is more than enough to go around) and simple ways to ensure that the economically vulnerable regained fuller participation in the economic life of this ancient society.

Beyond debts, slaves had to be freed, which placed a limit on the profit that could be made from them. And finally, the earth was to be given a year’s rest: a reminder that God gives more than enough in creation, and a period for the earth to recover from its misuse and the overtax accumulated over the years. six previous years. Considering all the ways a society can benefit economically from the poor and vulnerable, the Sabbath was God’s way of prioritizing freedom and restoration for all members of society.

I wonder to what extent the communal nature of the Sabbath is reflected in our practice today. Certainly, some of our leading guides on the nature and practice of the Sabbath—like Walter Brueggemann, Dorothy Bass, and many others—are eager to emphasize the communal implications of the Sabbath and the ways in which the Sabbath critiques and denounces injustice in our society (and in the church) to be accountable.

But unless our Sabbath practice extends beyond the personal and imagines and then dares to implement ways to extend God’s abundance and restoration to the most economically vulnerable – and to the most easily exploited – in our communities, I fear we are missing the fullness of God’s intentions for Sabbath.

We have much to learn from those whose work elevates our collective consciousness toward the experience of the poor and the interconnected nature of our lives in a shared society. It is Martin Luther King Jr.’s “unique garment of destiny.” idea at work. Or Melba Padilla Maggay’s notion that “the deprivation of one person is an indication of the guilt and humiliation of all.” As the prophet Jeremiah told God’s people in exile in Babylon, human flourishing is a shared responsibility (Jer. 29:7). The suffering of some extends to all of us, especially when it is due to participation in a society that extracts and exploits.

The Sabbath is a means for everyone rejoice in divine abundance. It is not simply a No towards unjust and unhealthy paths, but a reorientation of how and towards what, we say Yes.

What would change in our Christian witness and practice if we decided to create a way of life in the world that celebrates God’s abundance and experiences God’s restoration in a way that is centered on the experience of those who find themselves on the economic margins of our society? How might our practice of Sabbath rest foster a kind of sacred unrest at the ways in which people and places are exploited and at the barriers that prevent so many from experiencing the abundance of God in their lives?

Taking the Sabbath seriously enough to consider its economic implications for our lives and witness as Christians might involve asking what it means that Jesus is “Lord of the Sabbath” (Luke 6:5). Here it seems that Jesus is doing what he does with other Old Testament themes: in coming not to abolish the law but to fulfill it (Matt. 5:17), Jesus does not put an end to it. to these ancient ideas. Instead, Jesus inhabits these ideas in a new way. Instead of just adopting a rhythmic practice, Jesus embodies the ethos of the Sabbath and ushers in a new type of kingdom marked by the spirit and purpose of the Sabbath.

Jesus creates a world where the intentions of the Sabbath – perpetual delight in God’s abundance, continued restoration of the exploited, and inclusion of those on the margins into full participation in the community – are hallmarks of the way of life of God’s people in the world. world.

We see this way of life implemented in positive ways throughout the Book of Acts and elsewhere, as people live out the Sabbath ethic in tangible ways. They create common reserves of resources so that all can share in their collective abundance (Acts 2:42-47). They adapt systems and structures to accommodate the care and development of the poor and economically vulnerable (Acts 6:1-7). They consider how, in the case of Philemon, the reality of Christ makes Onesimus’ slavery seem discordant with the kingdom ethic established by Jesus.

On the other hand, Paul has harsh words for the Corinthian Church regarding the corruption of the community based on the exclusion of the poor and working class while the rich feast on their abundance (1 Cor . 11:17-22). This community embraced a version of the Sabbath ethic that undermined the new reality of life established by Jesus.

The world that Jesus brings into the world is worth our wholehearted investment, and the returns are abundant. The economic invitation of the Sabbath is an invitation to help shape a community where everyone, especially the most vulnerable, can taste and see this abundance and experience the restorative work of God.

The invitation to weekly rest is not just to stop and rest, but to inhabit the world with a sabbatical imagination, daring to build a world where, like Dorothy Bass said, “Injustice would not occur.” Jesus intends the Sabbath to extend beyond the rhythm of practice we establish for ourselves, animating a moral perspective that helps us say, with God: Enough is enough.

Adam Gustine is the author of Becoming a Just Church: Cultivating Communities of God’s Shalom and co-author of Jubilee ecosystems: economic ethics for the neighborhood. He works at the Institute for Advanced Study at the University of Notre Dame, where he focuses on scholarship in ethics and the promotion of human flourishing and the common good.