In the early 1970s, the Watergate scandal shocked the nation. One of the men involved was Chuck Colson, who later pleaded guilty and served time in federal prison. During this season, Colson came to believe in Jesus and converted to evangelical Christianity. In 1976, Colson published Born again, which recounts the events that led to his conversion and explains his radical change in life. The book was an instant bestseller, making Colson one of the most influential evangelical leaders of his time.

Also in 1976, a Georgia candidate named Jimmy Carter won the Democratic presidential nomination and then narrowly won the general election. Carter was barely known nationally, so his victory attracted even more attention. During his campaign, Carter declared himself to be a “born-again Christian.” Most political pundits and media outlets had no idea what that meant.

As the phrase grew in the public consciousness, many Americans assumed that born-again Christianity was a new Christian sect. However, as media outlets and pollsters investigated, they discovered that the phrase “born again” was simply used by ordinary evangelical Christians to describe the supernatural transformation people experience when they convert to Christianity.

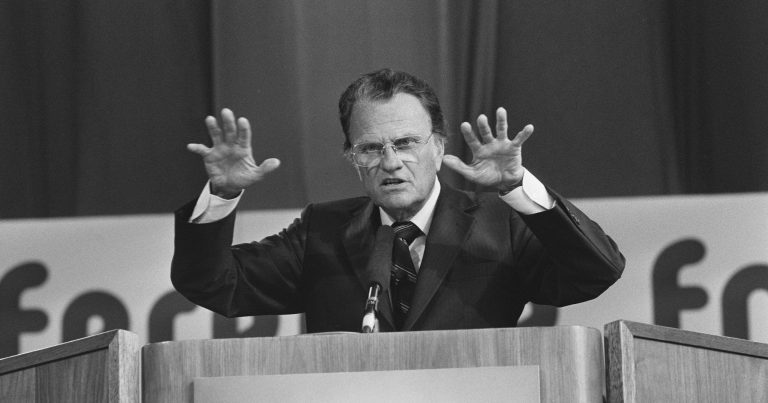

Evangelical Christianity was certainly not new, but when the phrase entered mainstream America, it increased the visibility of evangelicalism. The increased notoriety and influence of evangelicalism prompted News week review proclaim that 1976 was “the year of the evangelical.” The following year, world-famous evangelist Billy Graham published How to be born again. The book helped strengthen the credibility of the phrase “born again” and, more importantly, it sent the message that true biblical Christianity was synonymous with “born again Christianity.”

Modern or Antique?

Some commentators have claimed that the emphasis on born-again Christianity is an invention of the modern age. They asserted that the evangelical emphasis on the new birth was absent from most of church history. Evangelicals responded with Scripture.

Jesus said, “I tell you, unless one is born again, he cannot see the kingdom of God” (John 3:3). The new birth experience is also known as regeneration. The apostle Peter affirms that this experience is made possible by the work of Christ (1 Peter 1:3). The apostle Paul also associates the new birth with salvation and forgiveness of sins (Titus 3:4-7). Passages like these raise an important question: How can critics claim that born-again Christianity was a product of the modern age when the concept of the new birth so clearly comes from Scripture?

Most critics would certainly agree that the concept of the new birth is indeed in the Bible, but they would also argue that Christians of previous eras had a different understanding of the new birth than modern evangelicals. They would say that, for most of Church history, the time of the new birth was associated with infant baptism. In contrast, evangelicals associate the new birth with repentance and personal faith in Christ. Evangelicals believe that people are born again when they convert to Christ.

New birth in the history of the Church

It is true that the new birth has been associated with infant baptism for much of history. It is not true, however, that everyone in the early Church taught the new birth in this way.

In fact, several influential early church authors believed that the experience of the new birth was associated with repentance, confession, and saving faith. This includes the Epistle of Barnabas, Clement of Alexandria, Tertullian, Origen, and Hilary of Poitiers (see Gregg Allison, Historical theology, 649-67). However, as infant baptism grew in popularity during the third and fourth centuries, the vital association between regeneration and faith was greatly downplayed. Many medieval Christians believed that they had already experienced regeneration as children when they were baptized. So it seemed pointless to preach about being born again as adults.

REFORMATION

The Protestant Reformation placed emphasis on individuals believing the gospel, not just their participation in religious duties. The German equivalent of the term evangelical was coined by Martin Luther to describe Protestant churches that exhorted their followers to demonstrate genuine faith in the evangelical (gospel music).

The evangelical emphasis on the new birth was later greatly encouraged by the Lutheran theologian Johann Arndt. In the early 1600s, Arndt wrote True Christianity, which placed great emphasis on the new birth and godliness. The book was widely distributed across Europe for over a hundred years and had a huge influence on many future preachers, including John Wesley and George Whitefield.

GREAT Awakenings

In the mid-18th century, a series of powerful revivals swept America, led by the preaching of men like Jonathan Edwards and George Whitefield. Their preaching emphasized the new birth and called people to repentance. These revivals gave rise to American evangelicalism, which was an influential force in American society throughout the 18th and 19th centuries.

However, by the end of the 19th century, a divide emerged among so-called evangelicals, between modernists and fundamentalists. Modernists denied Christian orthodoxy and sought to reinvent Christianity in light of modern science. Fundamentalists have intensified their commitment to Christian orthodoxy, but they have also developed an activist posture toward culture. In the 1920s, these two groups were polar opposites.

Birth of a label

After the break between modernists and fundamentalists, modernists repudiated the evangelical emphasis on the new birth experience, but many fundamentalists redoubled their emphasis. They began to describe themselves as “born again Christians.” Although the phrase did not come into widespread use for several decades, it gained currency in some conservative Protestant circles during the 1930s and 1940s.

In the 1950s, a young evangelist named Bill Bright founded Campus Crusade for Christ, which became the most influential campus evangelism ministry in the country. Bright adopted the label “born-again Christian” and by the early sixties new converts in his ministry were also adopting this label.

Another notable segment of evangelicals who adopted this label were young adult converts to Christ as part of the Jesus People movement of the late sixties. Then Billy Graham began using the phrase “born again” extensively. Graham had been preaching since the 1940s, and he occasionally used the phrase, but in the 1960s the new birth vernacular became much more prominent in Graham’s ministry. The events of the 1960s put the phrase “born again” on the radar of almost every American Christian. And the events of 1976 then put this phrase on the radar of every American.

Born Again Appropriation

Another interesting phrase that entered the lexicon, over time, was “born again Catholic.” The new birth was generally a marker of evangelical Protestantism, but soon even Catholics began to report born-again experiences.

But for various reasons, these people wanted to remain in their Catholic tradition. The number of self-described “born-again Catholics” has been modest since the 1960s, but the number nearly doubled between 2004 and 2016 (see “Understanding the Rise of Born-Again Catholics in the United States” by Samuel Perry and Cyrus Schleifer) . . Although it may seem that a truly born again person can remain a devout member of the Catholic Church, there are some serious warnings to consider.

Additionally, by the late 1970s, the phrase “born again” was being used (and misused) by Americans to describe any transformative experience, even if the experience was not directly related to Christ and the Christianity. The phrase was used so frequently that when Bob Dylan was describing his own conversion to evangelical Christianity, he was reluctant to use the phrase “born again” because it was too “overused” (“overused”).John Lennon’s Born-Again phase“). A prime example of this is John Lennon calling himself a “born-again pagan.”

Faded label, crucial doctrine

So what is a born again Christian? Born again Christians are those who believe in the gospel, and therefore put faith in Jesus Christ for salvation, and who have experienced the supernatural transformation often called regeneration. They experienced a conversion from spiritual death to spiritual life. John Wesley described this experience as “a complete change of heart and life, from sin to holiness” (quoted in Thomas S. Kidd, Who is an evangelical?4).

This doctrine of the new birth occupied a central place in preaching among evangelicals and conservative Protestants in the modern era. This emphasis was not simply semantic. It inspired many people to make the new birth essential in their lives and ministry, which profoundly shaped the trajectory of American evangelicalism as we entered the 21st century.

Over the past twenty years, the phrase has declined somewhat in popularity, but the doctrine of the new birth remains a crucial part of the history and legacy of American evangelicalism. Additional labels will come and go, but the doctrine – and more importantly, the experience, if authentic – will remain.