When Corwin Smith began doing research while he was a graduate student in the 1970s, he says, “most academics thought at the time that religion had no real impact on politics.”

But less than a year after writing his thesis on political party identification, Jimmy Carter was elected president of the United States. For Smidt, “it kind of sparked a discussion about the role of religion in politics.”

Over the next few years, Smidt attended professional meetings in his field. It was there that he noticed that some researchers were using survey data and incorrectly classifying people religiously. One example he cited was an article in which a researcher used survey data to classify the United Church of Christ, a “liberal” mainline denomination, and a fundamentalist denomination. This misrepresentation didn’t sit well with Smidt, and he knew he had to do something about it.

Pioneer rather than colonizer

“I had gone to seminary for a year and my dad was a pastor and I was always interested in religion,” Smidt said, “so I thought ‘well, you know, this could be a field in which I can contribute and help the profession evolve. moving in a better direction.

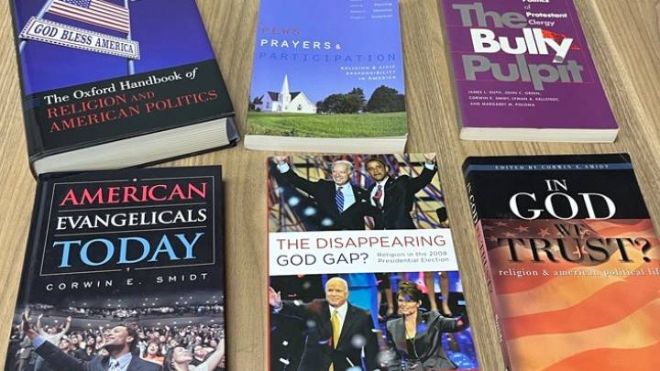

This question from Smidt turned out to be an understatement. He would spend nearly the next four decades in the “Gang of Four,” a group of scholars pioneering the study and research at the intersection of American religion and politics. Smidt and his three colleagues were honored for this work last summer, with the first Lifetime Achievement Award presented by the American Political Science Associationthe premier political science association in the United States and the world.

“These four individuals played key roles in the 1980s as they began to focus political science’s attention on the intersection of religion and politics,” said Kevin den Dulk, associate dean at Calvin University. “Not only were they innovative in using political science methods to show the impact of religion in public life, but they also began to bring together young scholars in ways that developed networks that became a subculture of political science. »

Smidt’s ability to accomplish this work was catalyzed by the creation of the Paul B. Henry Institute for the Study of Christianity and Politics at Calvin. He began teaching at Calvin in the late 1970s and was present when the Henry Institute launched in 1997. He served as the institute’s first director.

Paving the way for future professionals

“Almost anyone in their 40s, 50s and 60s who is doing empirical political science and wanted to think about the intersection of religion and politics took a seminar at the Henry Institute,” den said Dulk, who not only attended a seminar himself, but also succeeds Smidt as the institute’s second director.

Micah Watson is the current director of the Henry Institute. He sees how the foundation Smidt laid at Calvin continues to open opportunities for today’s students. “Since Corwin started at Calvin in 1997, I have compared our ability to provide opportunities for students in this field to anyone in the country,” Watson said, specifically citing the Civitas Laboratory, which pairs undergraduate students with renowned faculty on important research projects. “We have students who play in minor leagues with major league players, and then their names appear in an Oxford book.”

Integrate faith and religion

“The Henry Institute was created to be a place that would foster and sponsor genuine research and publications in Christian social science that would impact the field and be usable by members of the Church, educated laypeople,” said Watson said. “It’s this idea that religion and faith matter for public life, at the scientific level and at the level of the Church. These are not isolated from each other, but can and must inform each other.”

This idea of integrating faith and religion is not only central to Smidt’s work, but also central to the mission of Calvin University.

“We don’t neglect the things that matter,” Watson said. “An academic institution that attracts experts from all disciplines and deliberately brings them together better reflects the world in which we live. Calvin is not a Bible school, but it is trained and founded in faith, and we want to bring that faith into the world. , in history, in water policy and the drainage commission, because every square inch counts. One of the virtues of the Henry Institute draws on this philosophy and part of its mission is to promote this.

Passion and lifelong pursuit

Although Smidt retired from teaching after four decades at the academy, he remains a senior fellow at the Henry Institute. And his erudition does not slow down. According to Watson, “the guy is active enough right now to get a job. He’s involved in academia, doing things internationally in Serbia, the Netherlands and Romania, publishing articles on the 2020 elections, talking to churches, teaching a CALL course, that’s who he is, he still contributes to the institute and the mission of Calvin in a solid way. .”

For Smidt, it’s a labor of love. Even though he doesn’t do this work to be recognized, he is honored to have received such a prestigious honor for his life’s work. He is also grateful that over the past 40 years he has been able to help shape how and who the study of American religion and politics has been conducted.

Gain the respect of the guild

“It’s really humbling in some ways, and I’m appreciative in other ways, because it sort of recognizes a lifetime of research and writing that has now been appreciated by others working in the field,” Smidt said.

“Smidt and the three other members of the Gang of Four are well respected in the secular guild,” den Dulk said. “No one would consider them not being careful because they were motivated by their faith. Perhaps it is because of their faith that they are particularly cautious.