Will artificial intelligence destroy humanity or elevate it to new heights? Silicon Valley technologists are in a situation tumultuous debate on this same question.

Elon Musk, owner of Tesla and SpaceX, is working with his new startup, Neuralink, to develop neuroprosthetic devices, tiny electrodes implanted in the human brain that can connect us to computers and artificial intelligence (AI). The company received FDA approval conduct clinical trials on humans after its controversial testing on primates. It increases substantial funds to be competitive in this industry and make securities In the process.

Promoters claim they could treat quadriplegia or Parkinson’s disease or increase cognition and memory. Musk believes that thanks to this technology, we “will achieve symbiosis with artificial intelligence”.

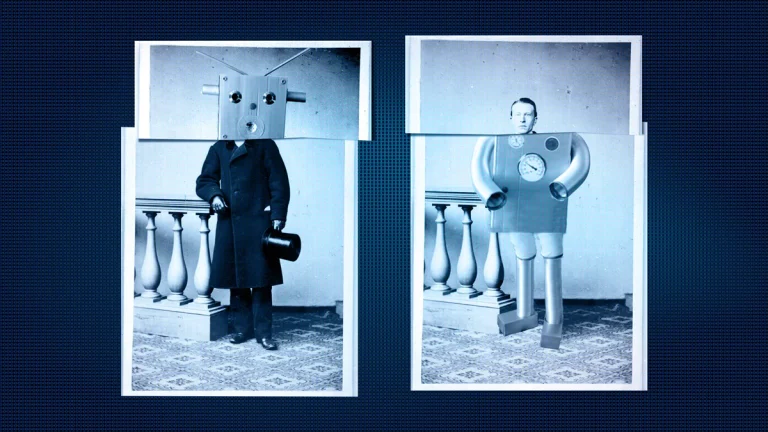

Despite their continuity with existing embedded technologies – such as glasses, hearing aids, pacemakers and smart watches – neural implants are the first devices allowing humanity to interact directly with machines. Such new territory often arouses either terrifying fears or great hopes.

Terrifying fear, or techno-pessimism, imagines a dystopian future in which human beings become dispassionate, dependent machines, while limitless hope, or techno-optimism, imagines a utopian future where technology will solve all our woes. This latter logic is stated as follows: AI cannot surpass human intelligence if we become one with it. In other words, if you can’t beat the AI, join it.

But whether technology inhibits absolute human freedom or promotes absolute human power, both assume that humanity is an absolute law unto itself.

Egbert Schuurman, a Christian philosopher of technology, believes that both techno-pessimism and techno-optimism are essentially religious in nature. Arguing that these views have to do with absolutes, Schuurman writing that “the fundamental choice on which this claim is based is radical and therefore has a religious character”.

For example, if you think that neural implants will destroy or deliver us, that is a religious thought. If the implantation of computer chips into our brains becomes our ultimate hope or fear, then it has become either our god or our eternal enemy. Either way, Schuurman points out, the conversation takes a religious turn. And humanity will never develop a proper relationship with this technology if we seek to let it determine our absolute hopes or fears.

As pastor and co-author of Reclaiming Technology: A Christian Approach to Healthy Digital HabitsI want us to think about how emerging technology could intersect with our theological framework. How can we think theologically about neural implant devices? Let’s consider three simple questions: Do I want this? At what price ? For whose benefit?

Do we want this? Theologian Norman Wirzba said we should always ask ourselves whether a new technology is really something we want.

“This stuff happens so fast,” Wirzba said of AI. “It has such appeal because the promises are huge and it’s very easy to get caught up in it. Because maybe it doesn’t align with the core values we should have.

The Bible says a lot about human ambitions and desires, and how our desires can often become our guardians. The Scriptures are full of people with misguided aspirations. Adam and Eve desired God-like freedom, but they later came to regret it. Israel wanted a king like the other nations only to be disappointed. Such stories can serve as a wake-up call to curb our impulsive instincts.

Desiring new technologies to alleviate human suffering and disease can be a noble and good goal. But even a purely altruistic motive can eventually transform into a goal of optimizing the basic functioning of the human brain. Do we want a future in which human thinking is indistinguishable from machine learning? Are we so dissatisfied with the human brain in its current state that we feel the need to increase our cognition and memory?

At what price ? We need to consider the ethical and societal costs that might arise from the commercialization of neural implants and determine whether the ends justify the means.

What humanitarian price are we willing to pay for the way clinical trials are conducted on human subjects? What societal price are we willing to pay if this technology leads to a significant divide between the haves and the have-nots?

The answers to these questions will reveal our ultimate priorities. Martin Luther said that a god is what we fear, love and trust above all else. If we are willing to sacrifice everything – financially, ethically and socially – to bring neural implants to market, then this emerging technology has become our god.

For whose benefit? Currently, neural implants are positioned to benefit people with clinical deficits, such as those with paralysis. But who will benefit when this technology reaches the broader consumer market?

Jesus calls us to love God while loving our neighbor as ourselves (Mark 12:30-31). By focusing on how neural implants might serve our fellow human beings – not just ourselves – we can better determine the value of this emerging technology.

It is very likely that neural implants will be commercialized before these questions are resolved, because neurotechnology companies are unlikely to think theologically about their creations. But as believers, we can think about the impact that emerging technologies might have on all of us.

Perhaps it starts by considering the impact of existing wearable technology on us. Has my Fitbit or Apple Watch brought more or less peace to my life? How does tracking my daily step count benefit my neighbor? What is actually driving my desire to have this next new wearable device like Apple Vision Pro?

Once we begin to think theologically about the devices we already wear on our bodies, we may be better prepared to ask much larger and more difficult questions, like what it might mean to implant devices into our brains. that help us become one with AI.

A.Trevor Sutton is a Lutheran pastor in Lansing, Michigan, and co-author of Redeeming Technology: A Christian Approach to Healthy Digital Habits.