California megachurch pastor and popular author John MacArthur recently denounced Christian nationalism is impossible because the Kingdom of God is not of this world. Now 84, MacArthur pastors a nondenominational church with premillennial Calvinist and Baptist (Christ comes before the millennium) and dispensationalist (end-times rapture theology, etc.) theology. Self-identified Christian nationalists are Calvinists, often Presbyterians, who believe in a Christian denominational state and are more inclined to postmillennialism in which the earth is subdued for Christ before his return.

Since MacArthur is openly theologically and politically conservative, many critics of Christian nationalism might assume that he is a Christian nationalist. In his recent commentsMacArthur sounds more like an old-fashioned Baptist separatist:

The Kingdom of God is not of this world. Jesus said, “My kingdom is not of this world. If my kingdom were of this world, my servants would fight. His Kingdom is not of this world. The kingdom of this world is a world apart. They are not linked to each other.

And:

Nothing that happens in a nation, whether it’s a communist nation, a Muslim nation, a quasi-Christian nation, quote unquote, or an atheist nation, nothing in that nation – politically, socially – has nothing to do with the advancement of the world. Kingdom of God. Because the Kingdom of God is separate from this system. God, in His sovereignty, is building His Church, and the gates of Hades will not prevail against it, Jesus said.

And:

So the idea that one should connect a political effort, a political process, a social process, a gain of power or influence in a culture as part of the advancement of Christianity is foreign to Christianity. Our Lord never approached anything like this, nor the apostles, and particularly the apostle Paul; he did not seek to gain any favor with the Roman Empire, nor indeed with any other ruler he had encountered during his life.

And:

Here we don’t win, we lose. Are you ready for this? Oh, you were a post-millennialist, you thought we were going to waltz into the Kingdom if you took over the world? No, we lose here, understand? It killed Jesus. It killed all the apostles. We will all be persecuted. If anyone comes after Me, let him do… what? – ‘deny himself.’ Prosperity Trash Gospel. No, we are not winning here. Are you ready for this? Just to clarify things, I like that clarity. We don’t win. We lose on this battlefield, but we win on the great, the eternal.

Self-identified Christian nationalists expect Christians of their view to “win here” before Christ returns by establishing a Christian denominational state that subdues public dissent from their brand of Christianity. Such Christian nationalists disdain the 20th The premillennial dispensationalism of the century, which assumes the role of the Church, is primarily about saving souls before the end of time.

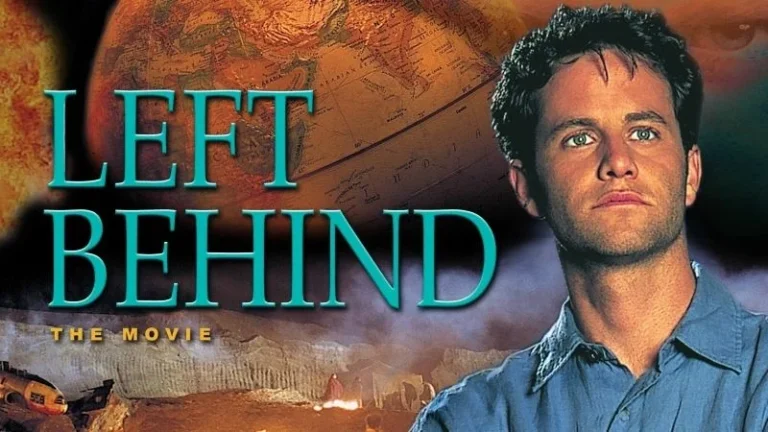

MacArthur’s Christianity has tens of millions of followers in America and has an enormous religious, social and political impact. The “Left Behind” literature and filmography reflect their views, as do evangelical shows like The 700 Club. The modern religious right, founded in the 1970s, shared his pessimistic view. They wanted greater political justice in America, as MacArthur does, to prevent divine judgment and allow more years of evangelism. But they neither claimed nor desired that a Christian nation could be established by law. (See my article on “Christian conservatism versus Christian nationalism. “)

Self-identified Christian nationalists are far fewer in number. They are more intellectual and subscribe to 16th and 17th century of Calvinist theories on the political government of the elected. They are obviously much more optimistic than Christian dispensationalists. But the latter have exerted broad political influence through voter mobilization and advocacy on certain issues, while the former have had little direct political influence, at least not yet.

Although still very influential, especially among Pentecostals, Christian dispensationalism is in decline. Its main promoters are, like MacArthur, older, retired or deceased. It is becoming rare to find young American Christians who are ardent dispensationalists. The emerging dominant perspective, common in much nondenominational evangelical Christianity, is amillennialism, which avoids choosing between premillennialism and postmillennialism. This perspective is typically pragmatic, focused on personal testimony and practical life, while avoiding the cosmic questions debated.

As Christian dispensationalism continues to decline, more and more Christians who have been taught a vague amillennialism will desire a more dogmatic and systematic alternative. Christian nationalism offers a solid road map for implementing God’s purpose through government. He gives clear marching orders to enthusiastic Christians who want to transform society. And while Christian dispensationalism warns of inevitable persecution and cataclysms, Christian nationalism proposes a government run by the right kind of Christians. Contrary to MacArthur’s warning, Christian nationalists are “winning” on the battlefield. This message can obviously be attractive, much more than that of “losing”.

And this resounding message can also lead to political failure and disenchantment. Christian realism warns against these dogmatisms. Christian dispensationalism has at times been prone to apocalyptic urgency followed by exhaustion. Christian nationalism seeks to systematize and implement what is probably beyond human reach. Both require certainty while mystery and patience are perhaps better.