It’s not subtle. This is also not planned.

Instead of a pastoral-looking nativity scene, the nativity scene depicts the baby Jesus wrapped in a checkered Palestinian kaffiyeh, surrounded by jagged pieces of stone – evoking the bombed buildings of the Gaza Strip and the children buried beneath.

“I see God in the rubble,” said Munther Isaac, the Palestinian pastor of a historic Lutheran church in Bethlehem, the West Bank city revered by Christians as the birthplace of Jesus. “And Christ was born under the occupation.”

Working with parishioners, he created the wartime painting, which will remain in place in the church throughout the Christmas period. The image is shocking, Isaac admits – but fails to summarize the daily horrors take place just 45 miles away, in Gaza.

The nativity scene at an iconic Lutheran church in Bethlehem, West Bank, depicts baby Jesus surrounded by jagged pieces of stone, reminiscent of bombed buildings.

(Marcus Yam/Los Angeles Times)

Palestinian Christians, a rapidly declining minority in the Holy Land, are celebrating a particularly somber Christmas this year, canceling festivities in a show of solidarity with their compatriots. Israel’s war against the Palestinian militant group Hamas keep grinding.

In this third month of Israeli bombing of Gaza, coupled with a large-scale ground offensive – both launched after Hamas attackers killed hundreds of Israelis in their homes and at an open-air dance festival – the death toll in this enclave The overcrowded coastal population numbers more than 19,000, or around two thousand people. a third of them women and children, according to Palestinian officials.

In Bethlehem, where many local Christians have family in Gaza, the Christmas holidays will be marked by prayers, religious services and the annual procession of Christian patriarchs – but the more joyful traditional trappings are avoided. No twinkling Christmas lights, no ornately decorated tree on Manger Square, no festive parade with marching bands.

People walk in the Old City of Bethlehem in the occupied West Bank.

(Marcus Yam/Los Angeles Times)

“How could we celebrate? » asked the city’s mayor, Hanna Hanania, whose office overlooks an almost deserted Manger square. The flagstone square facing the Church of the Nativity, a place of pilgrimage for Christians from around the world, is usually bustling at this time of year, but most of the souvenir shops and restaurants lining it are tightly closed.

Bethlehem, where once-majority Christians now make up less than a fifth of the city’s population of some 30,000, is a microcosm of the West Bank’s woes. Checkpoints surround it, and the stone terraced hills – where shepherds watched over their flocks at night, as the traditional Christmas carol goes – are crossed by an imposing Israeli security fence.

Surrounded by Jewish settlements, the city is home to two Palestinian refugee camps plagued by unrest and regularly attacked by Israeli troops.

“This is no longer the small town of the Bible,” said the Rev. Mitri Raheb, president of Dar al-Kalima University in Bethlehem. At 61, he remembers when the clear view from his nearby family home was a mountainside turning green in spring rains. Today, it is topped by a settlement, one of nearly 150 in the West Bank considered illegal under international law.

For Palestinian Christians, the current war marks a catastrophe within a catastrophe: the potential eradication of what was already a tiny Christian presence in Gaza. With fewer than 1,000 residents in a population of more than 2 million, the community’s wartime losses are felt disproportionately.

Many Christians in the Bethlehem area have relatives in Gaza and are terrified for their safety.

1

2

3

1. A man walks in the Old City near the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem. (Marcus Yam/Los Angeles Times) 2. People crowd a busy shopping street in Bethlehem. (Marcus Yam/Los Angeles Times) 3. A man sits near a mural on a wall separating Bethlehem from Jerusalem. (Marcus Yam/Los Angeles Times)

An outbuilding of Gaza City’s oldest operating church, St. Porphyrius, was hit by Israeli bombing in October, killing at least 16 of the hundreds of people sheltering there, according to Palestinian officials. Former U.S. Rep. Justin Amash, a Palestinian American, posted anguished social media accounts about several Christian relatives killed or maimed in the strike.

“Our family is suffering greatly,” the Michigan Republican-turned-independent wrote on X, formerly Twitter. “May God watch over all Christians in Gaza – and over all suffering Israelis and Palestinians, regardless of their religion or beliefs. »

Last weekend, two Christian women taking refuge in the grounds of a Roman Catholic church in Gaza City were killed by Israeli sniper fire, the Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem announced. Relatives identified them as a mother and daughter – Naheda Anton, 71, and her daughter, Samr Anton, 58 – and said that after the older woman was hit, her daughter tried to kill her. taken to safety and was also shot.

Jawdat Hanna Mikhail, grandson of one of the slain women and nephew of the other, said several other family members inside the Holy Family compound tried to reach the two women and were themselves shot.

“Snipers are deployed around the church,” said Mikhail, 27, who lives in Beit Sahur, just outside Bethlehem. “No one can move.”

Pope Francis condemned the murder of these women. A British MP, Layla Moran, posted on social media about members of her extended family, including 11-year-old twins, who were also stuck in the complex.

“I’m not sure they will survive until Christmas anymore,” she told the BBC.

Some longtime observers of Christian demographic trends say that after years of hardship, Gaza’s small, struggling community is on the brink of extinction.

1

2

3

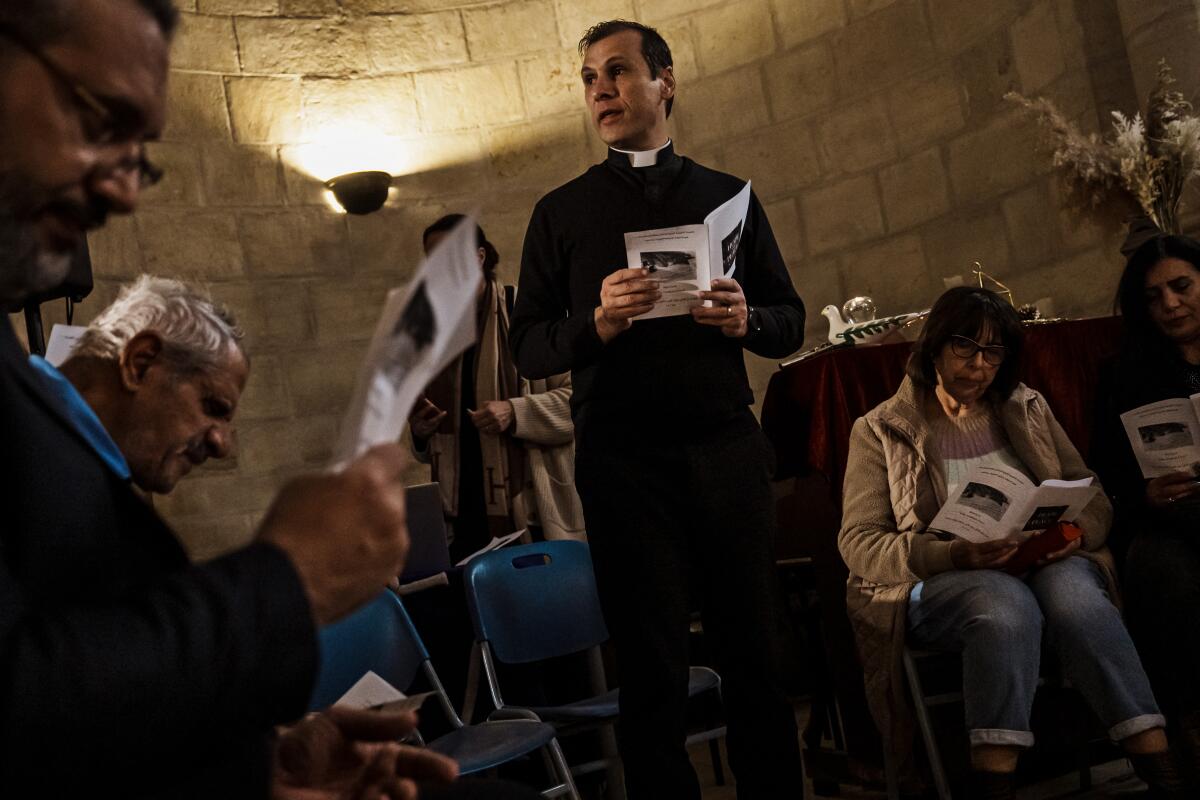

1. The Rev. Munther Isaac plays the flute at an iconic Lutheran church in Bethlehem. 2. Daher Nassar bows his head to pray. 3. Rev. Munther Isaac leads songs and prayers for Gaza victims. (Marcus Yam/Los Angeles Times)

“I fear that this war will mark the end of the Christian presence in Gaza,” said Raheb, the college president. “It’s a bleeding wound.”

The rise in violence also highlights the complex internal interaction in the occupied Palestinian territories between Christians and the overwhelming Muslim majority. Recent surveys suggest that Hamas’s popularity among Palestinians, both in the West Bank and Gaza, is rising despite – or because of – the devastating October 7 cross-border attack on Israel that precipitated the war.

Gaza’s Christian population numbered around 3,000 when Hamas took control of the narrow Mediterranean strip in 2007; about two-thirds of them left in the years that followed, before this war began.

Although they are generally wealthier and better educated than the population as a whole, Christians in Gaza have endured or been driven out by the same deprivations as other Palestinians – raging unemployment, lack of opportunities, periodic battles between Israel and Hamas. But they were also chilled by the unsolved assassination, at the start of the Hamas regime, of a prominent Christian bookstore director who had been threatened before his death by jihadist groups.

In Bethlehem, a decree from the Palestinian Authority, which governs the West Bank, requires that the city’s mayor, his deputy and the majority of city council members be Christian. Before that, a Hamas-backed coalition, which functions as a political movement in addition to its armed wing, held a majority on the council, the mayor said.

“They are our neighbors,” he said.

At the Church of the Nativity, an ancient limestone basilica revered by Christians as marking the birthplace of Christ, hard times have helped ease tensions between the three Christian sects that share control of its premises.

In recent years, jurisdictional disputes in the nooks and crannies of the church, in dark, incense-scented recesses, had sometimes escalated into physical altercations.

Father Issa Thaljieh, a 40-year-old Greek Orthodox parish priest at the Church of the Nativity, said there was now relative harmony between the sects, their conflicts largely overshadowed by the war.

Father Issa, born and raised in Bethlehem, said that from childhood he felt the powerful spiritual pull associated not only with the basilica but with the city itself, even as the ongoing conflict with Israel disfigured the landscape. biblical surrounding Bethlehem.

Father Issa Thaljieh poses for a portrait inside the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem.

(Marcus Yam/Los Angeles Times)

Although he could live and work elsewhere, he said he felt the call of duty to stay and care for his dwindling herd.

The deep sorrow over the death and destruction in Gaza permeates this holiday, the priest said, but he also sees this time as a much-needed glimmer of hope.

“These are very, very sad times,” he said. “But the message of Bethlehem and the message of Christmas, which is the message of peace, is more important than ever.”