In the Middle Ages, Christians spread their religion to the four corners of Europe. To subject new lands to Roman Catholicism, ancient pagan beliefs had to be destroyed. This is how it was done on the island of Rügen in the 12th century.

Our story is told by Saxo Grammaticus, a Danish cleric and historian who, around 1188, began writing the first comprehensive history of Denmark. Spread over 16 pounds, the Gesta Danorum dates back to Antiquity to tell the mythological beginnings of the Danes. It has long been popular reading for the tales and legends it tells relating to this region’s pagan past, as well as covering the rise of important rulers such as Cnut the Great.

As the 12th century approaches, the work focuses on the reign of various Danish monarchs, including Valdemar I, who was king from 1146 to 1182. While Denmark had long been a Christian country, some of its neighbors from the 12th century century The Baltic Sea region was still pagan, including the Wends, a people who inhabited the island of Rügen, located just off the coast of northeastern Germany.

After years of pirate attacks by the Wends, King Valdemar was persuaded by Absalom, the Bishop of Roskilde and chief royal advisor, to launch a crusade against them. The Danes landed at Rügen in 1168 and besieged the capital Arkona. Once Valdemar’s forces burned the city walls and buildings, the people of Arkona made a deal to surrender.

Once King Valdemar took control of Arkona and received hostages from the leaders of the Wendish people, he ordered the destruction of a statue of the local deity – a god named Svantevit. Saxon writes that men:

found themselves unable to wrench it from its position without the use of axes; They therefore first tore down the curtains which veiled the sanctuary, then ordered their servants to quickly take care of the destruction of the statue; however, they were careful to warn their men to exercise caution when dismantling such an enormous mass, lest they be crushed by its weight and be considered to have suffered the punishment of the malevolent deity. Meanwhile, a massive crowd of townspeople surrounded the temple, hoping that Svantevit would pursue the instigators of these attacks with his powerful and supernatural punishment.

After much work, the men took down the statue:

With a gigantic crash, the idol fell to the ground. The swaths of purple drapery that hung around the shrine certainly shone, but were so rotten with decay that they could not survive touch. The sanctuary also contained prodigious horns of wild animals, astonishing no less in themselves than for their ornamentation. A devil was seen leaving the innermost sanctuary in the guise of a black animal until he abruptly disappeared from the view of passers-by.

As the god of Arkona was being destroyed, the Danes received a message from the people of Karenz – another important city on the island – announcing that they too would surrender. Absalom went to the city with 30 men, where they were greeted by 6,000 warriors. However, the Wends bowed down to the Christians and welcomed the bishop.

Karenz was home to three pagan deities – Rugevit, Porevit and Porenut – considered the gods of war, lightning and thunder. Bishop Absalom came to destroy these gods, and Saxo Grammaticus (who may have been an eyewitness) describes the scene of his encounter with the first of the three pagan temples:

The larger sanctuary was surrounded by its own forecourt, but both spaces were surrounded by purple hangings instead of walls, while the roof gable rested only on pillars. Therefore our servants tore the curtains that adorned the entrance and finally got their hands on the inner veils of the sanctuary. Once these had been removed, an oak idol, which they called Rugevit, was open to view from all sides, of a completely grotesque ugliness. For the swallows, having built their nests under the features of his face, had piled up the earth of their droppings all over his chest. What a beautiful divinity, indeed, when his image has been so revoltingly sullied by birds!

Additionally, within his head were seven human faces, all contained beneath the surface of a single scalp. The sculptor had also provided the same number of actual swords in scabbards, which hung from a belt at the side, while an eighth was brandished in his right hand. The weapon had been inserted into his fists, to which an iron nail had clamped it with such a firm grip that it could not be torn out without cutting off his hand; it was the very pretext needed to cut it off. In thickness, the idol exceeded the width of a human body, and its height was such that Absalom, standing on tiptoe, could barely reach his chin with the small battle ax he carried.

Karenz’s men had believed him to be the god of war, as if he had the strength of Mars. Nothing about the effigy was pleasing to the eye, for its features were distorted and repulsive due to the crude carving.

Bishop Absalom ordered his men to begin destroying the gods:

Every citizen panicked as our henchmen began applying their axes to their lower legs. As soon as these had been cut, the trunk fell and hit the ground with a loud crash. Once the townspeople saw this sight, they mocked the power of their god and contemptuously abandoned the object of their worship.

Not satisfied with its demolition, the workers of Absalom all the more eagerly stretched their hands towards the image of Porevit, venerated in the neighboring temple. Five heads were implanted there, although they were fashioned without weapons. After this effigy was taken down, they attacked the sacred precinct of Porenut. His statue had four faces and a fifth was inserted into his chest, the left hand touching the forehead, the right the chin. Here again the servants did good service, cutting the figure with their axes until it toppled over.

After the idols were broken, the Danish bishop wanted to inflict more permanent destruction on the pagan gods:

Absalom then issued a proclamation that the citizens should burn these idols in the city, but they immediately opposed his order with supplications, begging him to have mercy on their overpopulated city and not expose them to the fire after he spared their throats. If the flames spread around and took over one of the cabins, the high concentration of buildings would undoubtedly cause the entire mass to go up in smoke. It was for this reason that they were ordered to drag the statues out of the city, but the people resisted for a long time, continuing to invoke religion as an excuse to defy the edict; they feared that supernatural forces would take revenge and cause them to lose the use of the limbs they had used to carry out the order.

In the end, Absalom taught them through his warnings to mock a god who did not have enough power to defend himself. Once convinced that they were safe from punishment, the citizens were quick to obey his instructions.

As the remains of the pagan gods were carried away, Sven of Arhus, another bishop who came with Absalom, added insult to injury:

To be able to show them that the idols deserved contempt, Sven made it a point to stand high above them while Karenz’s men hunted them. In doing so, he added an affront by increasing the weight and harassed the shooters as much by humiliation as by the added burden, when they saw their deities in residence lying under the feet of a foreign bishop.

During this time, Bishop Absalon prepared the region to become Christian. He first consecrated three burial sites in the countryside at the gates of Karenz and, after celebrating a mass, baptized the people. Saxo then adds: “Likewise, by building churches in a large number of localities, they exchanged the haunts of esoteric superstition for the edifices of public religion. »

The island of Rügen came to accept Christianity – and Danish rule. Bishop Absalon became archbishop of Lund in 1178, until his death in 1201. Saxo Grammaticus completed his Gesta Danorum in the early 13th century, covering his account of Danish history up to 1185.

Gesta Danorum: The History of the Daneswas edited and translated by Karsten Friis-Jensen and Peter Fisher and was published in two volumes by Oxford University Press. Click here to buy them on Amazon.com

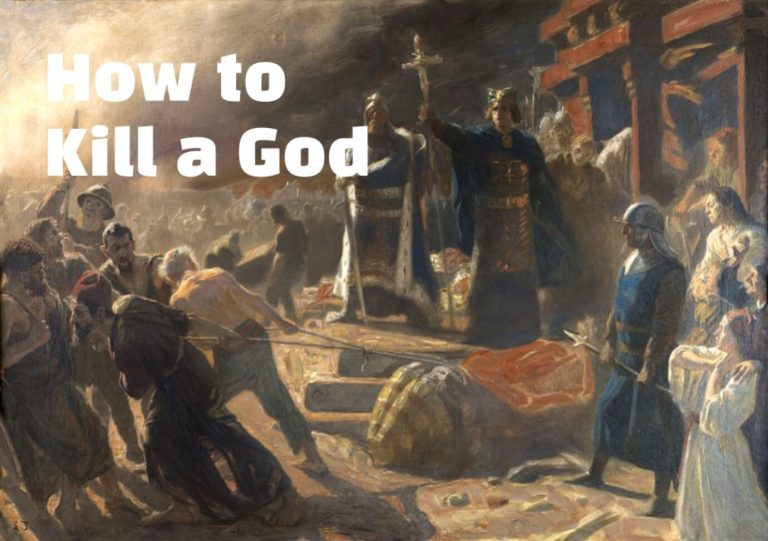

Top image: Bishop Absalom overthrows the god Svantevit at Arkona – created by Laurits Tuxen (1853-1927) – Wikimedia Commons