There were too many meetings.

When Mike Lowry became bishop of the Central Texas Conference of the United Methodist Church (UMC) in 2008, he also became responsible for governing two universities, two seminaries, a hospital and seven or eight others institutions.

“And I realized that I could spend my entire professional life in committee and board meetings without ever entering a church,” Lowry told CT.

The new bishop believed in the work being done by the Methodists, but it did not seem right that the episcopal role should be so fraught with bureaucracy. He felt bogged down.

“Bishops should be champions and guardians of mission and orthodoxy, not administrators,” Lowry said. “But the way the office was structured, it was primarily an administrative management position.”

In 2022, Lowry became the first bishop to leave the UMC and join the new Global Methodist Church (GMC). The question that led to separation, for Lowry and the more than 1.9 million Americans who LEFT between 2019 and 2023 there were same-sex marriages and LGBTQ clergy. In his resignation letter, Lowry wrote“The institutional expression of the United Methodist Church has departed significantly from faithful adherence to its own principles. Discipline and, even more, has departed from the full truth of the Gospel.

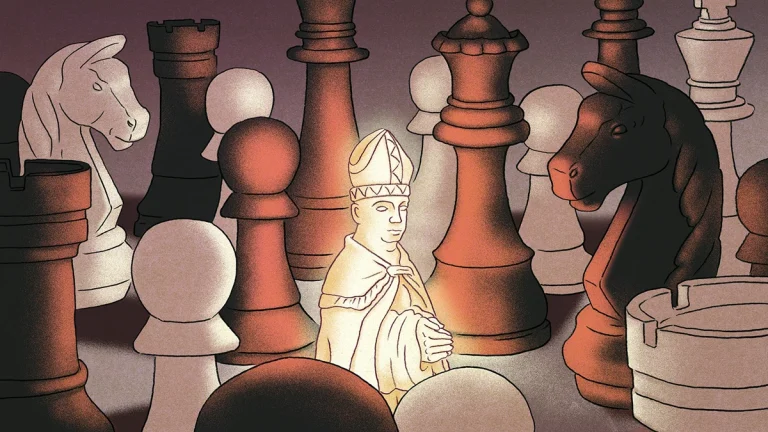

But the bishop and many GMC leaders also saw serious structural problems within the UMC. The Methodists had adopted a corporate model of church governance and bishops were becoming bureaucrats instead of shepherds. Then, when some leaders deviated from traditional teaching on matters of human sexuality, no corrective mechanisms were put in place to check their authority. The General Conference voted not to change the name Book of Discipline and retain the traditional position, but bishops in some areas announced they would simply ignore it and confirm LGBTQ ministers. And there were no consequences.

“I would say the separation was as much about authority and responsibility as it was about any theological issue,” said Keith Boyette, transition leader of the GMC.

Members of the new denomination are currently preparing for their first annual gathering, a General Convocation Conference, to be held in Costa Rica in September. They no longer debate sexuality. But they are grappling with the question of bishops and the form of the episcopate.

What should governance roles look like? What responsibilities should a bishop have? And, more urgently, Boyette asked, “What are you going to do to hold the bishops accountable?”

Some have been so hurt by the UMC hierarchy that they wonder “if the office is even salvageable,” according to Boyette. But the GMC does not plan to abolish the episcopal structure.

“You’re going to have someone who’s going to be responsible,” Boyette said. “You can call them something else – it’s not about the title; it’s about how you structure the office and how they’re selected and how they’re held accountable, but you’re going to have that person.

For a denomination that wants to reclaim an older expression of Wesleyanism, it also makes sense to build an episcopal governance structure.

“You can’t reject what you consider to be a revisionist position on marriage and at the same time embrace revisionism on something much more important,” said Ryan Danker, director of the John Wesley Institute. “Changing something as fundamental as the episcopate is a kind of reactionary pragmatism. This is not Methodism. You are no longer Methodist.”

The Methodist history of bishops is a bit complicated, however. John Wesley never became a bishop or called himself a bishop, but he believed he was ordained by God and exercised extensive authority over the Methodist movement, according to religious historian John Wigger.

Meanwhile, in America, Francis Asbury was ordained a Methodist bishop and claimed apostolic authority, but he was also elected by ministers at an annual conference.

“He took the title of bishop, but he made it more democratic,” said Wigger, who wrote a biography of Asbury. “In theory he was a bishop and his word was final, but in practice he negotiated. He was pragmatic. And much of his authority came from the fact that people viewed him as a servant, an old man on horseback with only one change of clothing.

For many faithful Methodists joining the GMC, these questions about bishops are brand new.

They know someone is attacking their pastor. But they have no political position. Some Methodist laymen say they only thought of the episcopacy when wondering about the mysteries of ministerial appointments.

Others say they never thought about bishops until a few years ago.

“Not until they tried to make us do things that weren’t right,” said Angie Fary, a member of Wesley Memorial Methodist Church in High Point, North Carolina.

Yet many desire to be part of a denomination with bishops. June Fulton, a lifetime member of Mt. Vernon Methodist in Trinity, North Carolina, said she was relieved when her congregation joined the GMC.

“The general consensus was we don’t want to be floating there,” Fulton said. “I thought we needed direction and to be connected to something. I thought it would work better for us, and almost everyone felt the same way.

Caroline Franks, the GMC minister currently serving in Mt. Vernon, said not having a bishop would be like “going out in the rain without a raincoat.”

But this year, GMC executives will have to decide what kind of raincoat they want. After all, they design it themselves.

David Watson, dean of the United Theological Seminary and one of the members of the GMC’s episcopate working group, said one thing under consideration is term limits. The convention could vote on a proposal that bishops would not be appointed for life but would be elected for six-year terms with the option of serving an additional term.

Many people within the GMC want congregations to play more of a role in choosing their ministers. Churches should not just accept bishop nominations. And the task force also plans to hand administrative responsibilities to the interim president and other leaders elected or hired by the general and regional conferences.

GMC bishops cannot be assigned specific regions. This way, they could focus on teaching and spiritual leadership without getting distracted by the details of day-to-day governance of a specific district. But perhaps they should be tied to one location, so that a bishop from Ohio is not tasked with overseeing the mission and orthodoxy of ministers in Kenya or a bishop from Bulgaria overseeing not a conference in Kentucky.

“This is all theoretical,” Watson said. “Everything must be ratified at the General Conference. We will decide these things as a Church. But now is the time to build, plan and work.

Although the question of the form of the episcopate has sparked discussion and debate within the young denomination, there is also a sense of unity, according to Watson. The details are still being worked out, but everyone agrees on the ultimate goal.

“The main thing people want to see,” he said, “is bishops as spiritual leaders who will preach and teach the faith, who will hold the people in their charge accountable and who will be them -themselves held responsible. »

Details are of course important, and some people have strong opinions about the right way to do things. The decisions the GMC makes in 2024 will affect the naming for years, even generations, to come.

There will undoubtedly be accountability challenges. And undoubtedly, for some bishops, too many meetings. But newly baptized World Methodists, hoping for a vibrant future, say the real test will be faithfulness.

“I think we need a good system of checks and balances,” said Laura Ballinger, co-pastor of First Methodist Martinsville in Indiana, “but if they love and follow Jesus and the Scriptures, everything is fine. “

Daniel Silliman is editor-in-chief of CT.

Do you have anything to add on this subject? See something we missed? Share your comments here.