By Nomia IqbalBBC News in Birmingham, Alabama

Ian Druce

Ian DruceWhen the Alabama Supreme Court defined frozen embryos as children, there was immediate shock and confusion. Major hospitals cut fertility services and expectant parents scrambled for clarity on what would happen next.

The debate over reproductive rights in the United States has long been driven, in part, by Christian groups’ opposition to abortion – but this decision has divided that movement and sparked debate over the role of theology in the development of American laws.

Margaret Boyce is a soft-spoken, reserved person and certainly not – in her words – a “screamer”.

She had been taking fertility drugs for 10 months and was days away from her first in vitro fertilization (IVF) appointment when judges on Alabama’s highest court turned her life upside down.

Their decision, which prompted many fertility clinics to suspend their work, led her to turn to the Bible daily for comfort.

“The journey to parenthood is different for every couple – mentally, emotionally and financially,” she said, speaking up.

“This decision has added even more unnecessary anxiety to something that is already so difficult.”

For a devout Christian like Margaret, the decision – given its consequences for what she clearly sees as a life-creating process – is even more difficult to understand.

“God,” she said, “is telling you to go forth and be fruitful and multiply.”

IVF is a difficult and lengthy treatment, involving fertilizing a woman’s eggs with sperm in a laboratory to create a microscopic embryo. The fertilized embryo is then transferred to the woman’s uterus, where it can result in a pregnancy, but success is not guaranteed.

Embryos are often frozen or ultimately destroyed in IVF, which accounts for about 2% of pregnancies in the United States.

The Alabama court ruled that an existing law – wrongful death of a minor – covers not only fetuses in the womb, but also embryos held in a laboratory or warehouse.

It did not explicitly restrict or ban IVF, but it nevertheless created deep uncertainty for clinics and medical personnel who handle embryos and fear prosecution. In recent days, the state attorney general’s office has said it has “no intention” of filing criminal charges against IVF clinics – but one clinic told the BBC that statement lacked detail and did not allay his fears.

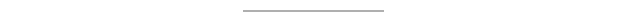

While the majority of the justices based their decision on the law, Chief Justice Tom Parker also had higher authority in mind, repeatedly invoking Scripture to explain his decision.

The people of Alabama, he wrote in a concurring opinion, adopted in their state constitution a “theological vision of the sanctity of life.”

Alabama Supreme Court

Alabama Supreme CourtDelving into the religious sources of classical Christian theologians like St. Thomas Aquinas and also a modern conservative Christian manifesto, he concluded that “even before birth, all human beings have the image of God and their lives cannot be destroyed without erasing its glory.

Some anti-abortion groups celebrated the explicit use of Scripture, in Justice Parker’s opinion, to justify what for them was a momentous decision.

Tony Perkins, president of the evangelical activist group Family Research Council, described it as “a beautiful defense of life.”

But the chief justice’s theocratic justification leaves Margaret perplexed. She doesn’t believe in abortion, but she also has difficulty considering a frozen embryo as a living person. For her, life begins with a heartbeat.

“No one understands better that an embryo is not a child,” she said before pausing, “than the person who longs for that embryo to be a child.”

U.S. courts sometimes make decisions that appear to be based on religious premises, said Meredith Bender, a professor at the University of Alabama Law School.

But, she added, “we rarely see it as explicitly” as in the chief justice’s opinion.

The ruling, however, is “not an exception” for a conservative court in a red state, said Kelly Baden, vice president of public policy at the Guttmacher Institute, which tracks abortion laws in the United States. .

“We find that many elected officials and judges often approach this debate from a highly religious angle,” she said.

While the Alabama State Supreme Court is not appointed by the U.S. president, more than 200 judges were appointed by Donald Trump to federal courts during his four-year term, earning him enduring support American evangelicals.

In four years in office, he was able to appoint three new justices to the nine-member Supreme Court, all of whom sided with the majority. overturning the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision which had guaranteed a federal right to abortion.

Since that 2022 ruling reignited a national battle over reproductive rights, Missouri courts have cited biblical teachings to justify restricting abortion rights and a Trump-appointed judge in Texas who previously worked for a legal organization Christian attempted to impose a national ban on reproductive rights. Mifepristone, a commonly used abortion pill.

Although many Republican politicians strongly agree with such rulings, abortion restrictions imposed by conservative courts have proven to be an important campaign issue for Democrats in recent elections, including mid-term elections. -2022 mandate.

Reuters

ReutersThe Alabama ruling, made by Republican judges and affecting fertility treatments widely supported by the American public, went even further, sparking immediate fear of a political backlash in a presidential election year .

Any sign of danger for IVF could deepen the anger that has already cost Republicans since the fall of Roe v. Wade, particularly among suburban women and those uncomfortable with the abortion ban .

Donald Trump himself, a clear favorite in the race for the Republican nomination, has spoken forcefully in favor of IVF, calling on Alabama lawmakers to preserve access to the treatment. Her latest rival, Nikki Haley, initially appeared to support the decision, but later backtracked.

“This is a philosophical victory for the pro-life movement because it perpetuates the pro-life recognition of unborn life,” said Eric Johnston, president of the Alabama Pro-Life Coalition.

“But you find yourself in a very difficult situation, where you have this medical procedure that is accepted by most people, and then how do you manage it? That’s the dilemma.

“I generally agree with the opinion. I think it’s a well-written opinion from the legal perspective and the medical side,” he added.

“But I think the pro-life community in general supports IVF, and I’ve known and worked with many people who have had children through IVF. And at the same time, they think abortion is a bad thing. This issue is so different from abortion. , but it has to do with life.”

What does the future hold for fertility patients in Alabama and beyond?

For patients in this Deep South state, the past week has been marked by panicked phone calls to clinics, emails to local lawmakers and a rush by some to try to transfer frozen embryos out of state.

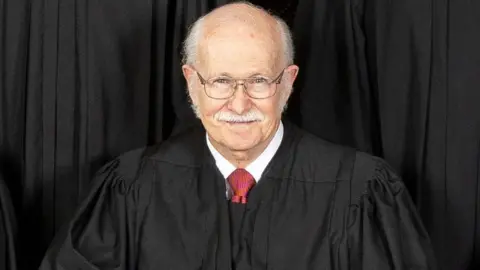

Rodney Miller, 46, and his wife Mary Leah, 41, spent a decade trying to have children, before IVF allowed them to give birth to a set of twins 18 months ago, who were adopted as frozen embryos.

He said he “thanked the Lord for the advances in science and medicine” that made this possible.

Ian Druce

Ian DruceThe couple is now starting the process again and waiting to see if the two embryos transplanted this week will result in a pregnancy.

“It’s not a victory (for the Christian right),” says Rodney, who works for Carrywell, an organization that supports families facing infertility.

“It’s the classic case where you won the battle but lost the war. Fewer children will be born because of this unless things change.

“How did we become a state where if you want to terminate a pregnancy, you have to leave the state and if you want to initiate a pregnancy, through IVF, you (also) have to leave the state?”

Whether Alabama’s decision will influence decisions elsewhere remains open.

Fetal personhood bills, which enshrine the idea that life begins at conception, have been introduced in more than a dozen states. But these bills, while promoting the idea that a fetus or embryo is a person, do not explicitly connect it to the context of IVF, said Kelly Baden of the Guttmacher Institute.

Alabama’s decision — with its implications that extend far beyond abortion access — therefore does not constitute a trend, she said.

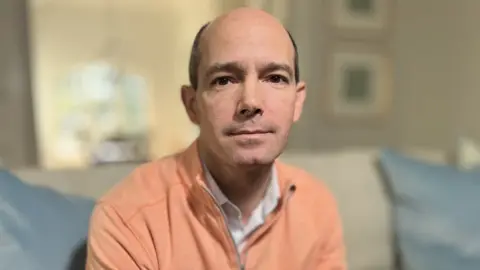

Ashleigh Meyer Dunham, a family lawyer in Alabama who has used IVF herself, has worked on many of the cases affected by the ruling. She said she was “terrified” that fertility patients in other states could potentially be affected.

Ian Druce

Ian Druce“I think the biggest concern is that people elsewhere will forget about us and think, ‘Oh, they’re just conservative states, and they’re all boors. Don’t worry, that’ll never happen here.’

“And the next thing you know, it’s happening in other ultra-conservative states.”

Because the Alabama decision involves an interpretation of state law and not federal law, it is unlikely to reach the U.S. Supreme Court. Currently, a bill is being considered in the Alabama House of Representatives, introduced by Democrats, that would seek to effectively suspend the decision and allow treatment to resume as before.

Republicans should propose their own bill. If they do, they must find a way to balance a divided religious community, with some celebrating the court’s decision and others concerned about its potential implications for IVF.

Margaret prays that lawmakers find a solution.

“I’m not very outspoken, I keep to myself. But if any of my friends or family found out that I was sending emails to every representative and senator, I think they would be shocked.”

She takes a breath.

“But it got me excited. That’s all I can think about right now.”

Alex Lederman contributed reporting from Alabama. Additional research from Kayla Epstein in New York.