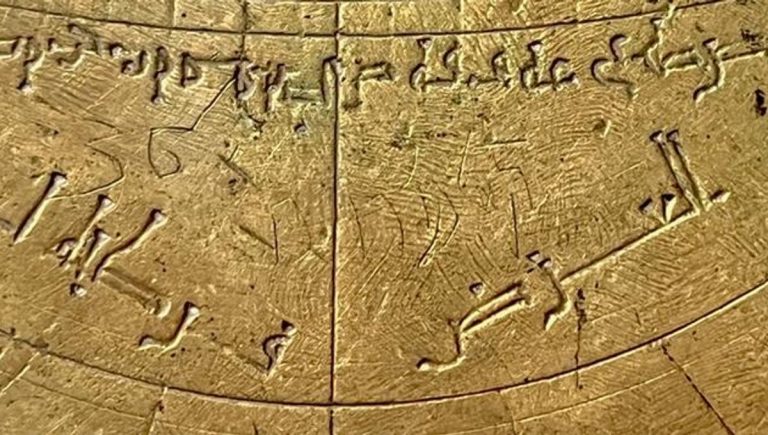

An elaborate artifact that was once used to tell time and calculate distances appears to have been used by members of three different faiths during its long and storied life. Known as a astrolabethe relic has been dated to the 11th century CE and bears inscriptions in Arabic, Hebrew and Western numerals.

Astrolabes are pocket-sized maps of the universe that allow users to plot the positions of stars. The engravings – which are clearly the work of several different people – were likely made in numerous locations in Europe and North Africa, suggesting that the object passed through the hands of Islamic, Jewish and Christian owners in the along his path. ancient scientific exchange networks.

Remarkably, the 1,000-year-old astrolabe was identified by chance when Dr Federica Gigante of the University of Cambridge came across a photo of the object on the website of the Fondazione Museo Miniscalchi-Erizzo in Verona, Italy. Italy. “The museum didn’t know what it was and thought it might be a fake,” Gigante said in a statement. statement. “It is now the most important object in their collection.”

After visiting the museum to study the astrolabe up close, Gigante was able to match the style of the original Arabic engraving to that seen on similar instruments from the region of Al-Andalus (now Andalusia) under Islamic rule in Spain in the 11th century. The position of the stars represented on the back of the astrolabe – or celestial map – also align with this period, thus corroborating the age of the device.

The ancient astrolabe contains a map of the stars.

Image credit: Federica Gigante

Muslim prayer lines are engraved on the metal relic, arranged to help the original user observe daily prayer times. One side of the plaque also contains an Arabic inscription reading “for the latitude of Toledo, 40°”, indicating that the astrolabe may have been made here at a time when Toledo was inhabited by large populations of Muslims, Jews and Christians.

The instrument also bears a signature including the names Isḥāq and Yūnus. According to Gigante, these could be Jewish names written in Arabic script, suggesting that the astrolabe could have circulated at some point within Spain’s Arabic-speaking Jewish community.

Another set of inscriptions depicting North African latitudes suggest that the object later traveled to Morocco or Egypt, while the presence of Hebrew letters indicates that it eventually returned among European Jews. “These additions and Hebrew translations suggest that at some point the object left Spain or North Africa and circulated among the diaspora Jewish community in Italy, where Arabic was not understood and Hebrew was used instead,” Gigante explained.

A final set of inscriptions including Western figures were probably made at the time by a Latin-Italian from Verona, the astrolabe eventually falling into Christian hands.

Summarizing the significance of this discovery in a new study, Gigante writes that “The astrolabe…stands out as a record of contact and exchange between Arabs, Jews, and Europeans during the medieval and modern periods. »

The study is published in the journal Nuncio.