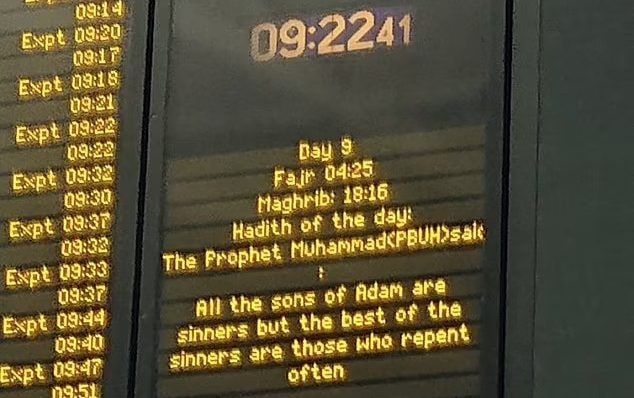

It’s a busy day on London’s main shopping street, and a young woman sings hymns. A police officer approaches and orders him to stop, saying: “You cannot sing religious songs outside the church grounds.” A few weeks later, and at a train station a few kilometers north of the shopping street, an electronic board displays a hadith – lines from the Prophet Muhammad – which says: “All the sons of Adam are sinners but the best sinners are those who repent often”.

While the Met later reprimanded the police officer over the Oxford Street hymn incident, and officials at King’s Cross station claimed on Tuesday that the ‘Hadith of the Day’ marked Ramadan, the holiest month of Islam, and also celebrated other religious holidays, notably Easter, these two episodes tell us a lot about Britain today. While other religions are respected, Christianity – this nation’s faith since the arrival of Augustine in 597 – appears to be in disgrace. In fact, it often seems that it is now treated by authorities as an anathema, an obstacle to progress, rather than as the foundation of the nation’s laws and culture.

Some of the most difficult dilemmas arise when one faith comes into conflict with other beliefs, as happened when a Leeds teacher, Andy Nix, preached in the street, openly criticizing what he called LGBT ideology. The police feared trouble, he was fined, then expelled by his school, but later obtained compensation. The case highlights the complexity of balancing a person’s freedom of expression with the common good. Yet these concerns have now led to a situation where a young woman on Oxford Street cannot even sing a devotional song without someone deciding that Christianity poses some sort of threat. Diversity is a good thing – but not when it comes to Christianity.

The denigration of Christianity has long been part of the liberal agenda, and many are vilified, for example, if they find abortion deeply disturbing. They are accused of being anti-feminist, but I don’t know why a law that allows disabled children to have abortions until birth is considered feminist. Christians are also condemned as insensitive if they are troubled by medically assisted dying, as if they want people to suffer. The fact that their concerns are about a slippery slope leading to elderly people dying is ignored.

Christian symbols and spaces are also contested. Years ago, the Radio Times had a special border on its pages with programs for Good Friday, with a cross in the image. This year, the cross – the very element that represents the crucifixion of Jesus that is commemorated every Good Friday – is gone and in its place there is a scampering spring lamb and a tiny church. Maybe they found it too painful or too, well, overtly Christian. Good Friday itself has become nothing more than a day of contemplation, fasting and abstinence: some restaurants have sent me an email inviting me to “celebrate” Good Friday with a hearty lunch.

But an entrepreneurial leader’s appetite to cash in on Good Friday is forgivable. Much less understandable is how churches dilute their Christianity. Anglican cathedrals, focused on tourism, fill their naves with dinosaurs and deranged people.

One of the most depressing indictments of the lack of enthusiasm among Christian clerics is the decision by St John’s College, Cambridge, to keep its Church of England chapel is free for regular services on Mondays. Apparently, this will “allow for other uses of the space and allow the dean and chaplain to advance student civic engagement and faith programs.” Anyone wanting to know more about civic engagement and faith surely need look no further than the services of the Established Church of England? Yet for St John’s College they pose an obstacle. And if representatives of the established church won’t defend Christianity, why will others take it seriously?

Officials treat Islam with respect, perhaps because they pick up on Muslims’ own feelings about their faith: they love and respect it with passion. If only more Christian leaders felt the same way about theirs.