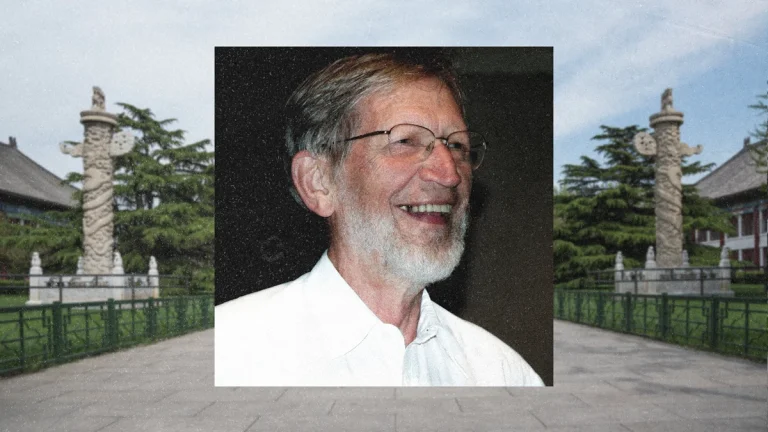

Alvin Plantinga is perhaps one of the most influential Christian philosophers in the West today. His accomplishments are astounding: he forcefully defended the logical problem of evil, launched the renaissance of Christian philosophy, reinvigorated apologetics, and deeply inspired many Christian scholars.

But what many in the West may not know is that Plantinga is also very well received by Chinese academics.

His magnum opus, GuaranteedChristian belief (hereinafter, subsequently WCB), was first published in English in 2000, then translated into Chinese by a team of Chinese scholars, some of whom were atheist philosophers, and published in 2005 by Peking University (the “Chinese Harvard”). The launch of the Chinese edition of WCB was held at the university to celebrate Plantinga’s 70th birthday. I was amazed by the respect and admiration Chinese scholars had for this Dutch-American philosopher.

At the academic conference that followed the book launch, an atheist philosopher was appointed to respond critically to Plantinga’s article. He began his response by saying: “The organizer of this conference owes me no thanks. Alvin Plantinga is my intellectual idol. Soon, Plantinga WCB has become one of the best-selling academic books in China. Plantinga later said that his work was even more to welcome in China than in the United States!

Reformed Epistemology Benefits Apologetics

Plantinga underlines this in WCB that arguments against the rationality of the Christian faith – which he calls “de jure objections” – are inseparable from arguments against the content of the faith – which he calls “de facto objections”. This implies that any de jure objection to Christianity must first disprove the truth of the Christian story, which is notoriously difficult to do.

In fact, arguments for and against Christianity assume two distinct epistemological histories.

According to the Christian narrative, the predominance of religious beliefs demonstrates the benevolent Creator’s desire for human beings to know Him – while affirming the human cognitive mechanism, which God designed for this very purpose. This epistemological story can explain theistic beliefs coherently and does not violate any standards of rationality. Therefore, Christians have the right to stick to their beliefs until proven otherwise.

The so-called Plantinga Reformed epistemologywhich is inspired by John Calvin and Thomas Reid, is a philosophical elucidation of this epistemological history.

Reformed epistemology asserts that belief in God and the gospel is fundamental and therefore their rationality does not depend on arguments or evidence. Plantinga does not reject the use of theistic arguments and, in fact, he endorses and develops some of them. But he maintains that, despite the absence of ironclad arguments, the strength of faith does not depend on the persuasiveness of the arguments. Otherwise, most Christians, who ignore theistic arguments, would be irrational in their beliefs.

Reformed epistemology is thus situated halfway between the excesses of rationalism and fideism, which can respectively lead to elitism and narrow-mindedness.

Interestingly, Plantinga believes that Karl Marx, arguably the most influential Chinese philosopher today, can help us see this idea more clearly. Marx believed that socio-economic factors can make human cognitive faculties dysfunctional or prevent them from achieving their goal. Here we can have the idea that the types of beliefs are produced by the cognitive faculties which correspond to them. It is therefore the quality of the relevant cognitive faculties – and not external evidence or reasons – that decides the rationality of beliefs.

In other words, as long as our beliefs come from properly functioning faculties, our beliefs are justified, even if we are not aware of the mechanisms that govern these faculties.

Now, returning to the Christian story above, widespread beliefs in God come from an innate faculty (sensus divinitatis) sensitive to the knowledge of its creator, but original sin undermines the functioning of this sense. Therefore, God – through special revelation and the work of the Holy Spirit – addresses original sin and forms a new faculty of faith, which cultivates belief in the great things of the gospel.

Analytical Philosophy Aids Theological Education

Next, I would like to focus more on Plantinga’s use of analytic philosophy in his works – which I believe has had a positive impact on theological education in China and other Chinese communities.

Analytical philosophy gives theology argumentative rigor, conceptual clarity, logical precision, and critical openness toward the sciences. And analytical philosophers are trained to detect ambiguous or inadequate definitions, fallacious arguments, and inconsistent statements. The various tools of philosophy can thus help believers effectively articulate difficult doctrines, such as the Trinity, the Incarnation, and the Atonement, to those within and outside the Church.

Plantinga’s translated works introduced the analytical approach to philosophy into Chinese seminaries in China and other parts of the world. In doing so, he initiated a renaissance of Christian analytical philosophy, which gave rise to Chinese-speaking analytical thinkers like The Kwan Kai Man (关启文), Andrew Ter En Loke (骆德恩), and others whose work benefits Chinese churches and seminaries around the world.

Furthermore, analytical philosophy can facilitate the more apologetic functions of theology, especially since scholars and students of engineering and natural sciences, who probably constitute the bulk of Chinese intellectuals, find the analytical method more compelling on the intellectual level.

Relatively speaking, theological education in Chinese communities is still developing, and analytical tools can help seminarians develop a healthy critical spirit that defuses fanaticism and anti-intellectualism. In this age of widespread misinformation and polarization, Chinese seminary educators are increasingly aware of the importance of logic and critical thinking.

As in the West, Christian theology in the East has been heavily influenced by continental philosophy, and so learning about a different philosophical tradition can enrich theological works with new perspective and ideas. For several years I have been introducing analytic philosophy to seminarians and pastors in Asia and have found the analytic method useful, not only for systematic theology and apologetics, but also for more practical courses like hermeneutics, homiletics and spiritual disciplines.

One of the fundamental tools of analytical philosophy is conceptual analysis, which aims to discover the precise meaning of the terms we use.

In his works, Plantinga offers insightful analyzes of several concepts, including God, free will, knowledge, and faith, which help readers see the rationality and appeal of Christian beliefs. In simple terms, to analyze a concept X is essentially about discovering the basic components of X. According to his analysis in WCB, for example, the concept of knowledge contains both the elements of true belief and warrant. In other words, one can claim to know God if, and only if, one has a justified true belief about him. And a belief is justified if, and only if, it is produced by cognitive faculties that function properly in an appropriate environment.

Conceptual analysis is important because we can often take our religious concepts for granted. These concepts can be overused and become cliché or even import foreign components and become easily manipulated for non-religious purposes. Those who teach and preach must realize that the scriptural concepts they use may not reflect the original meaning found in Scripture – or even if they do, they may not have the same meaning for the original audience.

These gaps can lead to subtle errors that can increasingly distort Christian doctrine and practices. But armed with sound logic, conceptual analysis can become a disciplined practice of discernment. This can help resolve issues that vex Christians, such as how to differentiate faith from superstition, loyalty from dogmatism, hope from wishful thinking, and love from sentimentality. And by helping believers discover the implications of theological concepts, conceptual analysis can enrich their theological understanding.

According to Plantinga’s defense of free will, having libertarian freedom logically implies the ability to do otherwise. Thus, God cannot choose to create a free Adam or Eve without risking falling into sin: divine omnipotence does not imply the ability to perform logically impossible actions (for example, doing 1+1= 3). For example, God could create a flying human being, but God could not commit suicide or commit sins, because doing such things would be impossible for God, as the most perfect being. God’s logic transcends human logic, but if God can violate logic, then God could contradict himself, which is logically inconceivable.

It is sometimes said that, compared to the Western mind, the Chinese way of thinking is intuitive and not analytical. But this account is challenged by the fact that Chinese philosophers, in particular Mohists (Mojia) and the School of Names (Mingjia, “Logician”), were among the world’s first proponents of logic and semantic theory. Even Confucius, China’s most revered philosopher, advocated the rectification of names or terms (Zheng Ming), which can be understood as an examination of concepts. For, he says, “if names are not rectified, then words cannot have meaning, but if words do not have meaning, then things cannot be established. »

As Wang Anshi, a Confucian of the Song dynasty, writes: “The scholarly debate is about concepts and their referents; if clear coherence between the two can be achieved, then the truth about the world can also be obtained! While Chinese philosophy is more practice-oriented than Western philosophy, Mohists and Confucians believe that correct practices rely on examining and correcting our concepts. For this reason, the use of Plantinga’s analytical method is not only compatible with Chinese culture, but it can also facilitate the formation of contextual theology in Chinese churches.

Leonard Sidharta (Dai Yongfu) is associate professor of theology at GETS Theological seminary.