By Yolande KnellBBC News Middle East correspondent

BBC

BBCAlthough Christmas may be a distant memory for many, Armenians in Jerusalem have only just celebrated their annual celebration on January 19th.

This year, the holiday was overshadowed by the war in Gaza and the continuing threat to the community’s survival from a deeply controversial real estate deal.

Many spent the day unconventionally, joining a sit-in under a tent in the parking lot of their church, part of a large endangered plot of land in the Armenian Quarter of the Old Walled City.

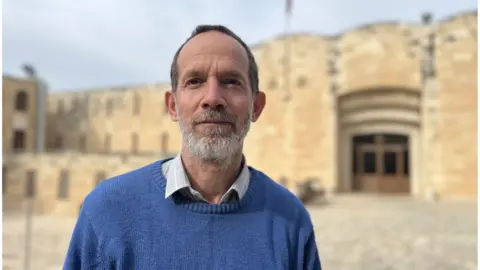

“This illegal and dangerous land deal brought us all together,” says Setrag Balian, a ceramicist turned activist.

Armenians date their presence in the holy city back to the 4th century. Many of the community’s 2,000 members live inside the large cobblestone complex of St James’s Convent.

In the past, they have often been divided by political differences and family conflicts, and divisions have emerged between Jerusalem’s Armenians and their ecclesiastical leaders, who serve as employers and landlords for many.

Yet for the past two months, local Armenians and priests have all stayed here 24 hours a day in a large makeshift tent to try to block development. They eat here and work shifts as guards behind a makeshift barricade decorated with Armenian flags.

Together, they say, they repelled attacks from bulldozer-wielding contractors, armed settlers and masked thugs.

“With this deal, everything was put at risk,” says Setrag. “Whoever wants to deprive us of our rights and endanger our presence and our lives here, we will stand up against them and defend our rights to the end.”

Last April, facts began to emerge regarding a 2021 contract secretly signed between the Armenian Patriarch and an Australian-Israeli Jewish developer. He gave a newly formed company, Xana Gardens, a 98-year lease to build and operate a luxury hotel in an area known as Cow’s Garden.

The agreement covered a plot of land of 11,500 m², adjoining the walls of the south-western part of the old city, with an option to acquire an even larger area.

It includes the parking lot, some religious buildings and the homes of five Armenian families, representing approximately 25% of the Armenian neighborhood.

Situated on Mount Zion, it has enormous religious significance and is an incredibly valuable piece of real estate, but an annual fee of just $300,000 (£237,000) had to be paid by the developer.

“For that amount, we could barely rent a few falafel shops in the old town,” commented an Armenian using the parking lot, who asked that his name not be used.

Amid strong protests from the local population and the decision by Jordan and the Palestinian Authority to withdraw recognition of the Patriarch for his role in the deal, pressure has increased on the Church to cancels the contract.

Meanwhile, an international team of Armenian lawyers came to investigate and give advice.

The patriarch claimed he was deceived by a trusted priest who was later defrocked. He finally announced a formal decision to cancel the deal in October.

At that point, tensions between the Armenians and representatives of the developer – whose workers had taken possession of the parking lot by force – began to turn into direct clashes.

When Israeli bulldozers arrived at the disputed site to attempt to begin demolition, Armenians rushed to block it. The following month, allegations of intimidation arose when the promoter arrived with several armed men.

Further attempted incursions took place after the protest tent was set up. The most violent took place last month, when masked men came to the parking lot beating people with sticks and using tear gas. A priest, Father Diran Hagopian, broadcast the events on Facebook Live.

“They were shouting: ‘You should leave this country,'” he later told the BBC. “One of their leaders was shouting, ‘You can break their legs, you can even kill them, but they should leave.'”

The apparent involvement of known Jewish settlers in the attacks, alongside other evidence, has heightened long-standing suspicions that a powerful settler organization was involved in the attempted land takeover.

Since Israel conquered the Old City and its holy sites from Jordan in the 1967 Middle East War, Jewish investors in Israel and abroad have sought to purchase properties in an attempt to consolidate Israeli control. on occupied East Jerusalem.

The Palestinians want this part of the city to be the capital of their hoped-for future state. Israeli Jews consider the entire city their eternal and undivided capital.

Researchers at the Israeli nonprofit Ir Amim, which focuses on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and supports Jerusalem’s diversity, are concerned about developments in the Armenian neighborhood.

“It’s close to sensitive places,” explains Aviv Tatarksy. “Creating a settlement in this area is part of the very ambitious goals of settler organizations who basically want to completely Judaize the Old City, with their eyes fixed on the Temple Mount or the al-Aqsa Mosque.”

Settlements built in the occupied territories are considered illegal under international law, although Israel disagrees.

The BBC contacted the developer behind Xana Gardens several times, but has not heard back.

The now-defrocked American priest who coordinated the deal, Baret Yeretsian, was surrounded by a crowd of angry young Armenians shouting “traitor” as he left the St James Convent last year, assisted by Israeli police, before moving to Southern California.

He has since denied to journalists that the promoter has any political or ideological agenda, calling the accusations “propaganda” based on his Jewish identity.

The Armenian Church has now initiated proceedings in Israeli courts to challenge the validity of the contract for the Cow Garden.

As residents gathered around a brightly lit Christmas tree in their makeshift tent last week, they remained determined but were aware that their legal fight could easily take years.

It remains to be seen whether the incursions can be stopped in the meantime.