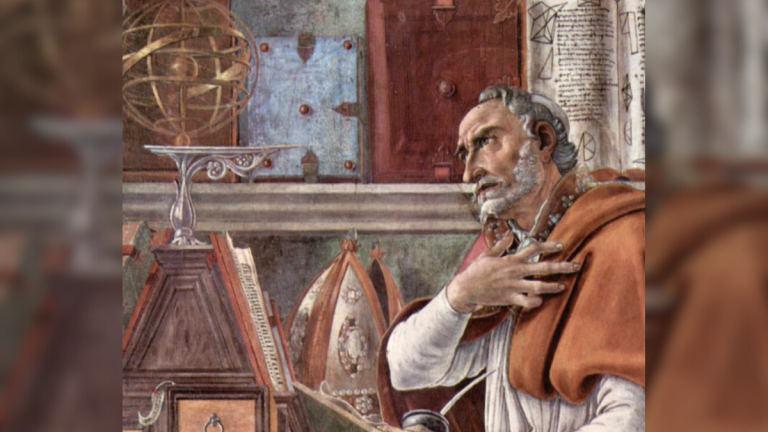

From the earliest days of the Church, Christian theologians have marveled at the paradoxes found in the incarnation. One of the earliest expressions of this wonder comes from St. Augustine, the most influential theologian in Western Christianity.

Augustine was born in 354 in Thagaste, a Roman city in modern Algeria. A brilliant thinker, he initially rejected Christianity as an intellectually empty faith, despite his mother’s loyalty. After having explored various pagan philosophies, the no less brilliant Saint Ambrose, bishop of Milan, showed him how Christianity was superior to pagan philosophies. Augustine became a Christian and eventually returned to Hippo, where he was elected bishop.

Augustine was an expert orator. He was a professor of rhetoric in Milan when he met Ambrose. As a Christian, he used his intellectual abilities and communication skills to address both the pressing theological questions and conflicts facing the Church in the late 4th and early 5th centuries as well as the challenges posed by opponents of Christianity. He also used his impressive skills in his preaching. During his many years as bishop of Hippo, Augustine preached numerous Christmas sermons that dealt with various aspects of the incarnation. One of his most striking sermons addresses the many paradoxes involved in God taking on human flesh. For example, in what we call Sermon 184which Augustine delivered sometime before 396 AD, he highlighted the paradox of God’s sovereignty with the vulnerability of becoming a child:

He who keeps the world in existence lay in a manger; he was both a voiceless child and a Word. The heavens cannot contain him, (again) a woman carried him in her womb. She ruled our sovereign, carrying the one in whom we are, nursing (the bread of life).

In Sermon 191delivered years later in 411 or 412 AD, Augustine was even more pointed on the incarnation paradox:

Creator of man, he was made man, that the director of the stars might be a child at the womb; that the bread may hunger and the fountain thirst; that the light may sleep and the path be weary with the journey; that the truth may be accused by false witnesses, and that the judge of the living and the dead may be judged by a mortal judge; that justice may be convicted by the unjust, and discipline scourged with whips; that the bunch of grapes may be crowned with thorns, and the foundation may hang on a tree; that strength might weaken, that eternal health (might) be injured, that life (might) die.

Like his listeners then, Augustine would have us consider in the incarnation what we so often neglect in our familiarity with history. He also encouraged an appropriate response to the great mystery of the incarnation. In sermon 184 he says:

Let us therefore celebrate the Lord’s birthday with all the necessary festive gatherings. Let men rejoice, let women rejoice. Christ is born, a man; he was born of a woman; and each gender was honored. Now therefore, let each one, having been condemned in the first man, pass on to the second. It was a woman who sold us death; a woman who gave us life.

As Augustine explained, Jesus came in the form of sinful flesh so that our sinful flesh would be cleansed. This shows that it is not the flesh itself that is at fault, but the sin that corrupts it. This sin must die so that we can live. Thus, Augustine affirmed the created goodness of the body, and with it, the goodness of Creation. He also reminded his listeners that Jesus was born without sin so that we who have sin could be born again by faith.

Not everything in Augustine’s Christmas sermons is so theologically clear, but we would do well to meditate on his words about the wonder and many paradoxes of the incarnation and join him in celebrating and rejoice at the birth of our Lord.

This Breakpoint was co-authored by Dr. Glenn Sunshine. For more resources for living like a Christian in this cultural moment, visit breakpoint.org.