What is Easter about? In some ways, the answer is quite simple: Jesus Christ and the Christian belief that He rose from the dead.

In other ways, however, spring break is far from simple. How are rabbits involved? Where does the name “Easter” come from – and why is the English word different from the way many other cultures refer to this holy day? Even theologically, the exact meaning of the resurrection is not universally accepted.

Here are four articles that dive into the history of Easter, its meaning — and what a rock ‘n’ roll Broadway show has to do with it.

1. Choose the date

First things first: Easter is what’s called a “moveable holiday,” a holiday whose exact date changes from year to year. In the Northern Hemisphere, it falls shortly after the spring equinox, as the world blooms again – an auspicious time to celebrate rebirth.

But Easter meetings “goes back to the complicated origins of this holiday and how it has evolved over the centuries,” wrote Brent Landau, researcher in religious studies at the University of Texas at Austin. Similar to today’s Christmas and Halloween celebrations, Easter mixes elements of Christian and non-Christian traditions.

Mario Tama/Getty Images

The name “Easter” itself seems linked to a pre-Christian goddess named Eostre in what is now England; it was celebrated in spring. And in fact, in most languages the word for the holiday is related to Passover, since the Gospels say that Jesus went to Jerusalem. to celebrate the Jewish holiday in the days preceding his crucifixion.

But “celebrating” Easter itself has not always been fashionable among Christians. For the Puritans, Landau explained, these holidays were considered too tainted with revelry and non-Christian influences. As 19th-century American culture embraced the idea of childhood as a special time in life – not just preparation for adulthood – Christmas and Easter became popular occasions for spending time with family .

Leia but:

Why Easter is called Easter and other little-known facts about the holiday

2. Sacred hares

The biography of the Easter Bunny, however, begins well before the 1800s. The famous fertility of rabbits and hares has made them symbols of rebirth For thousands of years. Some were ritually buried alongside humans in the Neolithic, for example.

Of course, this fertility also makes them sex symbols, as anyone who has seen the Playboy logo knows. “In classical Greek tradition, hares were sacred to Aphrodite, the goddess of love,” explains the folklorist. Tok Thompson, professor at USC Dornsife. The goddess’s son, Eros, was also depicted carrying a hare “as a symbol of unquenchable desire”, and even the Virgin Mary is often painted with a rabbit, to symbolize how she overcame desire.

A painting by the artist Titian (1490-1576), Louvre Museum, Paris.

Modern traditions of the Easter Bunny originate from folk traditions in Germany and England, and there is evidence that the symbol of the goddess Eostre was also the hare.

3. Victory over death

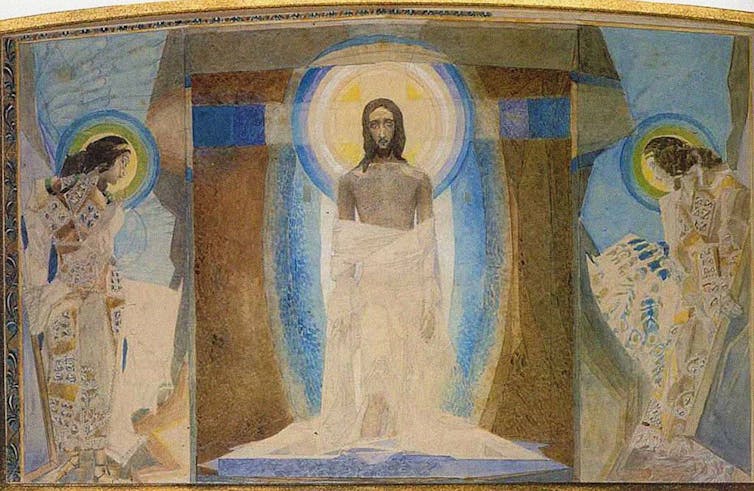

Holy Week, the series of events in Christian churches leading up to Easter, traces the final days of Jesus before death and resurrection, including Palm Sunday and the Last Supper. Easter Sunday itself is the climax of the story: its triumph over death.

“As a Baptist minister and theologian myself, I believe it is important to understand how Christians in general, and Baptists in particular, have different points of view on the meaning of the resurrection,” wrote Jason Oliver Evansdoctoral student at the University of Virginia.

Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Hulton Art Collection via Getty Images

Over the centuries, Evans writes, Christians have had “heated debates about this central doctrine of the Christian faith” and what it means for Jesus’ followers – for example over whether his body was literally resurrected from the dead.

4. Superstar

There are many ways to share the story of Holy Week – and one of the most controversial debuted on Broadway in 1971.

“Jesus Christ Superstar, the rock musical by Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice, has struck some Christians as blasphemous with its modern retelling of the Passion and its “Jesus is cool” philosophy. Then there is the end of the show, which stops after the crucifixion – removing the Resurrection and its theological message entirely.

Blick/RDB/ullstein image via Getty Images

However, a half-century later, “Superstar” raises fewer eyebrows – a reflection of changes in American culture and Christianity, writes Henri Bial, professor of theater at the University of Kansas. Perhaps this shouldn’t come as such a shock: as he pointed out, theater and drama have always been linked to biblical stories.

Leia but:

Best Easter competition ever? Half a century of “Jesus Christ Superstar”

Editor’s note: This story is a roundup of articles from The Conversation archives.